Istanbul Institute of

Russian and Sovietic Studies

The people of Russia, except few rickety events, remained indifferent to the centenary of the 1917 Revolution and spent the November 7th 2017 like a normal day. According to a survey commissioned by the Communist Party, 58% of the Russian population was unaware of the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution (1).

Whereas Nov. 7th was a holiday celebrated by big ceremonies, during the Soviet era.

The editor of the independent Russian TV channel, documentary filmmaker Mikhail Viktorovich Zygor proclaimed that he was very surprised by the fact that the Russian press remained indifferent to the centenary of October Revolution (2).

The Russian President V. Putin, four days prior to Nov. 7th (in November 3, 2017), said that the October Revolution was a complicated episode of their own history and that these course of events should be treated with respect in an unbiased way (3).

The media star, candidate for 2018 Presidencial elections, also famous by her public kissings, appearing in many TV programs, Ksenia Sobchak announced that – if elected president – she would take the Lenin’s mummy away from Kremlin and bury it to the cemetery. Ksenia Sobchak is the daughter of Anatoly Sobchak who brought Putin to political life during his presidency of municipality in St Petersburg between 1991 – 1996.

Sobchak’s statement started a big polemic with the centenary of the October Revolution. Chechnya president Ramzan Kadyrov supported Ksenia Sobchak’s idea saying that Lenin should be granted to peace by his embalmed corpse being burried.

One should carefully think about these statements and the identity of their correspondent leaders: let us remember the Chechenian X Russian War that was conducted throughout 90’s by the separationist/nationalist Dzhokhar Dudayev… and then there was no the so called “nationalist” Putin in the governance of Russia. There was instead Yeltsin, who was applauded by the liberals. Today, however, there are “nationalist” leaders on both sides. These leaders, as they cooperate in Donetz and Lughansk issue having taken a common position against the Ukrainian separationism, they also share a common opinion against the Bolshevik Revolution.

On the other hand, the Russian Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov proclaimed that even voicing to removing the Lenin Mausoleum should be considered “blasphemous” (4).

One should especially pay attention to the wording of Zyuganov as well: he chose the word “blasphemous”. The so-called secular, communist leader supposed to carry humanity to a higher level of consciousness adhered a religious and iconic discourse against the Kadyrov + Putin stance.

Russian people however, were not interested in this debate that was going on at the level of politicians. 100th anniversary of the October Revolution was celebrated with tiny demonstrations at the few corners in the cities without public care and attention. And we should note that people were even more disinterested in the 101st anniversary (7 November 2018).

The Westerners’ Great Love for Revolution in Russia

The situation was by contrast very differrent in the US and in the UK, especially at the center of the financial capitalism, in the city of London. The British and the Americans celebrated the 1917 Revolution more than anyone else in the world.

The US centenary leading propaganda organ of the ‘Red Scare’, the New York Times, had instantly been converted into a ‘militant Bolshevic’ by publishing a serial of articles it called ‘The Red Century’. The serial had consisted of 40 articles in total, applauding and celebrating the centennial of the Russian Revolution. Besides few serious ones, the majority of these articles were based on a left-wing intellectual rhetoric promoting an hysterical romanticism for bolshevism:

Sarah Jaffe, in her article investigating the effects of 1917 to the US, claimed that communism was compliant with Black people’s spirit. With this assignment, she invented and advocated the ‘black communist racism‘ as a new kind of racism.

Yuri Slezkine speaking of Sverdlov, promptly shifted into telling us about the loves of the finance minister Osinsky and associated it with the authentic revolutionary spirit.

The Bard College faculty member Sean McMeekin who is also a well known scholar by the students of Bilkent University in Ankara and Koç University in Istanbul, tried hastily to convince us that “It does not matter whether Lenin was a German spy or not!” …

Having been determined to teach the greatness of The Russian Revolution to the Russians, the so-called “public intellectual” Tariq Ali praised Lenin. And David Priestland praised Trotsky. Let’s note once again that both Tariq Ali and David Priestland are from the city of London.

Caryl Emerson defining Putin as the new face of Stalin, advocated us reading the 19th century Russian writers in order to cope with him. Emerson’s article reminded us – as we will explain below – the Iskra Magazine issued by Parvus + Lenin partnership in 1900 by the money raised by selling Russian writers’ books in Europe.

The New York Times’ The Red Century constituted an examplary case for running a coordinated ideological endoctrination operation led by the authors labelled as “left-intellectuals”.

We have translated many of these The Red Century articles into Turkish and published them in PDF format in Istanbul Institute of Russian and Sovietic Studies homepage. Their English originals are still available in the NYT’s webpage.

In London, on the other hand, an art (painting) exhibition called “Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932” was organized in The London Royal Academy of Arts, between February 11, 2017 – April 17, 2017:

Let’s carefully examine the introduction leaflet of this organisation exhibiting the “great” paintings of the Bolshevik Revolution, the sublime masterpieces of Kandinsky, Malevich, Chagall, Rodchenko, etc. and let’s check how the expressions are chosen in this catalog, to penetrate into the amygdala of the ‘intellectual’ brains, that is, the targetted audiences:

- – One hundred years on from the Russian Revolution, this powerful exhibition explores one of the most momentous periods in modern world history through the lens of its groundbreaking art.

- – ended centuries of Tsarist rule and shook Russian society to its foundations.

The above phrase “shook Russian society to its foundations” has been set intentionally using a wrong preposition (“to” instead of “by”) to create an ambiguity associating that the Revolution had turned the Russian society back to its natural state, i.e. a nomadic, a non-centralist structure that they “deserve”.

- – Revolution turmoil, brought with it its own destiny in their own hands to discuss how the field of public art. But unfortunately this was no air of optimism when the bride 1932, he finished creativity in art under Stalin’s repressive dictatorship.

- – Amidst the tumult, the arts thrived as debates swirled over what form a new “people’s” art should take. But the optimism was not to last: by the end of 1932, Stalin’s brutal suppression had drawn the curtain down on creative freedom.

These statements showed that the Western elite, who used to describe all revolutions as deviations from the natural course of history during 1990’s, has now discovered the value of the Russian Revolution and moreover, they hastly try to teach their discovery, to the Russians who are unaware of the value of their own Revolution.

We published the contemporary sociological and economic analysis of this phenomenon in our article “The Goose’s Foot is Scalloped” (too much work to translate this huge article into English, so please read it using a webpage translator!). And this time, we investigate the historical background of this phenomenon.

So, why no social scientist, no “intellectual” question this odd situation where British and Americans celebrate the Russian Revolution more than the Russians in Russia?

This question is still not asked aloud, as the tale of ceaseless, repetitive Trotskyist doctrine of “permanent revolution” which atrophies leftist minds, repeating the myth that the Bolshevik Revolution was universal even if it started in Russia it should have spread throughout the world.

We, on the contrary, question exactly this hypocrisy plastered with leftist romanticism. The day when the Leftists come up asking the above question avoiding mythological narratives, they will learn to be the real Left without being pawn for divisive ethnic/identity politics.

In addition to above cited oddities, again in London, in honor of the 100th Anniversary of the October Revolution, a committee called The Russian Revolution Centenary Celebration Committee was formed to organize various events.

This committee has organized several conferences and panels telling how important was the Russian Revolution. Then they did film screenings they named “SPARK Film Festival” consisting of early Soviet films about the Bolshevik Revolution.

The Dirty Story of Iskra Newspaper

Here, let us also note how names are continued as to become a tradition:

Iskra is the name of the newspaper issued by Lenin and Alexander Parvus from 1900 until 1905. Parvus is a merchant of death (arms dealer) who has also been known by other names like Lazarevich Gelfand, a professional communist revolutionary. Iskra means spark in Russian. It is likely that this name had been found by Parvus. It is taken from a poetry of Alexander Odoevsky titled From a spark the fire will flare up (Из искры возгорится пламя) during the Decemberists uprise in 1825.

Upon the enaction of the surname law in TR, it is said that one of the leftist sects’ idol in Turkey, the “great theoretician” Dr. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı had chosen his surname after this newspaper name.

Iskra Newspaper was prepared in the apartment of Parvus, in Munich. The border town Pskov was chosen as the main distribution base for the newspaper. Pskov is a pivot area interchangeably occupied at frequent intervals since the time of the Teutonic Knights and Alexander Nevsky.

The editorial group who settled in the apartment of Parvus were deciphered in a short time by the Russian secret service and their activity was stopped by the German police in 1902. Parvus and the editorial group, where among them was also found Plekhanov, had to move first to London and then to Switzerland.

Although the bosses of the newspaper Iskra were both Lenin and Parvus, Lenin’s meeting with Parvus has always been narrated as an enigma. We know that Lenin was a very jealous and weak-minded man. Did Lenin perceive Parvus as a rival to him (as he did, later in Capri days, with Bogdanov) and therefore avoided to come face to face with Parvus? Or -contrary to common belief- did Parvus not take him into account and didn’t care coming face to face with Lenin who had no public base? We expect the historians will find answer to this question.

However, during these transitions from Munich to Switzerland, the Parvus + Lenin meeting took place, again in London.

English sources describe Parvus as a figure who sometimes appear included and sometimes banished from the Bolshevik gang because of raising polemics and having no clear role in the Revolution. The fact that Parvus was the inventor of ‘permanent revolution‘ attributed to Trotsky has recently been admitted. Rather than the personal connections and the actual mission, the so-called “theoretical” aspects of Parvus’ contribution are brought to the forefront.

Intellectual elites has long been fascinated by the word “theory”. Having exchanged ‘doctrine’ with ‘theory’, the contemporary intellectual and academic elite undertook the same role of the magicians and monks of the past times.

Parvus played this role very well too. Having invented the concept of “permanent revolution” they had found a way for fitting Marx into their agenda for Russia: the revolution might have first started in a backward country like in Russia (the spark), nevertheless this might then have ignited greater revolutions in well-developed capitalist countries (the fire). We see Parvus avoiding to face concrete and realistic questions like “what next, after the revolution?” and drowning the debates into abstract concepts associating to an ambiguous configuration of mystical dynamics that would presumely drag the world towards a better future (5).

Marx was thus twisted to fit their agenda for Russia.

As the uprisings today are manufactured through internet and social media fake news, Iskra Newspaper used the power of lie too: In 1904, when Japan declared war on Russia, Parvus wrote that the tsarist regime had been responsible for the outburst of the war. Parvus told that the war had been desireable for Tsar to suppress the internal unrest. He asserted that imperialism had been the latest phase and the military phase of capitalism (Alexander Parvus, Iskra, February 10th, 1904). This “military stage“; “final stage” kinds of “stage” discourses that Parvus invented were then coppied and pasted by Lenin in 1916, in his book “Imperialism, the last stage…” besides being inflated by extra fillings taken from Hilferding’s “Finance Capital“.

Elisabeth Heresch mentiones that, Russia at that time, was not among the signatories of the copyright law in Europe. Parvus saw this legal gap (or someone had shown him this legal gap) and he made the books of 19th century Russian writers translated and commercialised to a variety of European languages in Europe. Parvus earned big money out of this business. However, Parvus had used the members of the party for the translations of the books. It is likely that he also used Plekhanov who was a strong pen and a multi-lingual. According to their agreement he should have transfered the 60% of the earnings to the party. But Parvus went on vacation to Italy and spent all the money. This deteriorated his relation with Gorki.

So what made Rosa Luxemburg + Karl Liebknecht couple to still endorse Parvus despite his crook attitude? The background of the sabotage of Grimm Peace Plan in Switzerland by Parvus in 1916, his intricate connections with the German and also most probably and simultenously with other Western countries’ secret services, his multilateral espionage missions are still dark. These issues has recently been studied by the German + Russian historian Elisabeth Heresch.

The facts that Parvus was the financier of the Iskra newspaper, and that the first issues of the newspaper were prepared in the apartment of Parvus in Munich, including the Parvus <> Plekhanov connection, such phenomena -for some reason- are still not visible in English sources.

Why ?!

Is that for not overshadowing the 100 years pulverised perception of the October Revolution legend?

Plekhanov‘s dogmaticaly recognized article The Role of Individual in History article, the various names that appear in this article and their connections too, should all be taken into an autopsy re-study in light of the newly opened Soviet archives. With what motive did Plekhanov write this article? Who were the minds behind him?

The details like Plekhanov’s connection with Parvus in Munich through the Iskra Newspaper and Parvus’s founding of the newspaper appear in the work of the German + Russian historian Elisabeth Heresch. While Elisabeth Heresch’s all books have been translated into Russian she is still quite unannounced and unpopular in the Western world. Her book revealing the dirty facts about Parvus “Geheimakte Parvus: die gekaufte Revolution : Biographie” is published as an open source in Russian, without copyright restriction on the internet (6).

From Parvus to Sergei Eisenstein, the fantasy of mass movement

While no one remembers the Eisenstein-labeled film ‘October‘ (1928) in Russia, it’s screening in London was promoted as a very special event as part of the SPARK film shows. It has been expressed that the film ‘October‘ was particularly “repaired” for those impressions. The Film was released in London’s famous Rio Cinema, Phoenix Cinema, which are known as “independent” and somehow profit free or charity undertakings (7).

While investigating the reasons why British and Americans embrace the Russian Revolution in Russia more than the Russians, it is also worth to ask why the film ‘October‘ — since it was produced — was far more promoted in the West than in Russia. The film ‘October‘ was not just a simple product of Eisenstein. It’s an application of mass manipulation techniques developed by Parvus, and before then, in Lenin’s meeting on Capri Island with Gorky and other Bolsheviks, and even before then, dating back till the 16th century Commedia dell’Arte tradition.

It is partially true that Commedia dell’Arte had initially appeared as a satirizing art to rulers. However it has almost immediately transformed to a powerful ideological apparatus used by rulers. Even the first generation of these comedians were kept for money and commissioned to entertain people by the Bavarian Lords in holidays and carnivals. So the bragging left intellectual’s, the so called “authentic art” was already commodified since the beginning of the 15th century. These are historical facts to which left intellectuals — who are celebrating the “art” of theater as “the authentic revolutionary art” — are still unable to confront.

Mikhail Bakhtin‘s huge work Rabelais and His World, therefore, distinguishes the revolutionary notion of ‘grotesque‘ from the regressive notion of ‘carnavalesque‘ into Commedia dell’Arte tradition, emphasizing that the regressive ‘carnavalesque’ always prevails.

Professor Zizek warns about the need of a mind to reveal this distinction between Carnavalesque X Revolutionary referring to the failed events like the colored “revolutions” in Georgia, Ukraine, the Arab Spring, square occupations, including the Gezi uprise in Turkey. He says he would “sell his mother to slavery” to watch the second part of the infamous film V for Vendetta:

And here is the film Eisenstein’s ‘October’ is simply an older version of ‘V for Vendetta’. The film ‘October’ could never be continued too, since October 1917 had in fact continued by the killing of 10 million Russians and with the hunger, cold and diseases for the survivors in a country which was torn apart by a civil war. This is why October 1917 is not remembered in Russia today, while it is celebrated in the AngloSaxon world.

One should seek, however, the Revolution in Russia, not in 1917, but after 10 years, namely in the developments beginning from 1928: re-establishment of the bond between the countryside and the urban; the collectivisation of the agriculture and the establishement of agrarian cooperatives (kolkhoz); the liquidation of the intermediary classes, the NEPman, that is, the blood-suckers of the paesantry; the re-building of the centralist state and the territorial integrity; and so on…

The preparations for the 10th anniversary, including the story of the making of the film ‘October‘, show that the motto of left-intellectualism — “the revolutionaries should establish ties with people” — could have only be achieved after 1928 and that 1917 was nothing but just a regressive counter-revolutionary coup d’etat (against Stolypin-Witte agrarian reforms).

In 1927, the Soviet government established an organisation named “October Revolution Jubilee Committee”. Nikolai Podvoisky was assigned as the Chairman of this committee. Nikolai Podvoisky was one of the bolsheviks who played an important role for the invasion of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg during the October Revolution. According to a recently uncovered archive documents dated November 16, 1917, Nikolai Podvoisky too, was financed by the money sent from Germany, like Lenin and Kamenev (8):

Nikolai Podvoisky asked the prominent film directors of the country to make films to be shown at the 10th anniversary celebration of the October Revolution.

The government however – while ordering these films for the 10th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution – was under a heavy debt load. For the payment of this debt, the most precious artworks in the museums, palaces and churches were sold to western countries. The estimated total value of these artworks sold to the West were worth to 50 billion gold rubles (9).

The discourse to legitimize this looting of artworks was ready at hand in the Trotskyite doctrine: the art that was made prior to the Revolution was “bourgeois art” and therefore it should be liquidated.

The tenth anniversary of the Revolution was, on the other hand, the dawn to major transformations: the Trotsky X Stalin conflict had then rekindled on their controversy on how to deal with the problems of NEP. The NEP that was put into force in 1921 was supposed to be “provisional measures” to recover the economy before shifting to “socialism”. However up till 1927 it was then revealed that the Bolshevik gang had never had any sound transition plan and that the ultimate purpose was to perpetuate it. Eventually, Trotsky tried to sabotate the three commissions which were established to deal the problems arising out of NEP. Here we think Trotsky’s primary concern was Dzerzinsky who was assigned to direct one of these commissions and who had – previously – conducted a victorious “spies’ war” against the British intervention in Petrograd during the Civil War. Trotsky asserted – as usual – abstract “theoretical” arguments against “centralism” hiding the real concern, trying to obscure the core of the problem. This initiated his fall: he was expelled from the Politburo and the Central Committee. He and a group of his supporters organized a demonstration in Redsquare, which Krupskaya too was attended, in the immediate aftermath of the 10th Year celebration. This show remained ineffective, it didn’t attract public support. They remained alone in the Square. The following year, Stalin put an end to the NEP.

It was exactly in such a political atmosphere that the 10th anniversary celebrations were being held and that the film director Sergei Eisenstein got the order.

Let’s also briefly remind here the constellation which brought this order to Eisenstein:

In its first impressions, Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film Potemkin was too bad to be watched. As it didn’t attract any public interest, it was shown just in Moscow, in just one cinema, and just for a week, then ended up being thrown to the warehouse. Despite this fiasco, in the following days, with the intervention of Mayakovsky the full 45 km negatives were taken from the warehouse and to be sent to Berlin.

Piel Jutzi, the famous German film director in Berlin was commissioned to make a film out of these negatives. Re-assembling the negatives, Jutzi managed to form a viewable film of 1.7km in length, which is the film ‘Potemkin‘ we know today.

The film premiered in Berlin with a huge international publicity campaign that was carried out by Embassies, cultural missions, art elites, with the participation of Hollywood celebrities and dignitaries. The “expert” commentators of world leading newspapers and magasines in London and in the United States too, they immediately and simultaneously began propagating the film as a big art event, a cinematic masterpiece.

In our main article “Understanding the prodigy of Sergei Eisenstein” we have already detailed these events.

Consequently having arrived in 1927 Eisenstein was still floating on the fame that was fabricated for him in Berlin through this international operation a year ago. Thus the project ‘October‘ (Ten Days That Shook The World) was offered to him through this wind of fame.

The screenplay was formed out of the memories of the American socialist John Reed’s book (1919) “Ten Days that Shook the World”. But it is often told that Eisenstein’s film was made in a surrealist perspective.

The realities versus the surrealities

The film was completed in six months. A total of 49,000 meters of negatives were used. Out of this amount, a total length of 2000 meters were chosen to form the edited movie. The film’s release date was set to November 7, 1927.

Meanwhile, the gap between the actions and the rhetoric of the Bolshevik gang had been deepened. Thus, this “surrealist” depiction of events in 1917 didn’t get the support from the government. The Committee didn’t like the film.

According to the memories of Grigori Aleksandrov (the co-director and the close mate of Eisenstein), during the last preparations of the film Stalin entered their room and ordered them to remove all scenes about Trotsky. As they had no time to make an adequate re-assembly, the film was shown in the Bolshoi theater in cropped way and nobody liked it, thus, soon removed from vision (10).

The film was then revised and begun to be shown in March 1928 in cinemas.

In the film Eisenstein has shown the Winter Palace being occupied by a large crowd.

In reality, however, the Winter Palace was occupied by a very few number of armed militants and with the help of a traitor inside ordering to the female guard battalion not to resist to offenders.

For those days when the film was being shown, the memories about the so-called ‘The Great October Revolution of 1917’ were still fresh in people’s minds. Therefore people didn’t interested in in those visual propaganda stuff displayed as “art”. Some scenes like the toothless elderly bourgeois beating the revolutionary guys with umbrellas and canes were particularly been ridiculed. As the film was contradicting to Stalin’s art doctrine (the socialist realism) too, it was thrown soon again to the stockroom to be erased from the history of cinema.

The film was however peculiar with it’s one feature: Lenin was for the first time played in scene. The player was an ordinary worker with name Vasily Nikandrov working at Lysva Metallurgical Plant. Before the release, Eisenstein’s close friend Mayakovsky watched the movie and commented for the player that “he looks more like a statue of Lenin rather than Lenin himself” (11).

The Female Guards Battalion and Eisenstein’s misogyny

During the Lvov provisional government in February 1917, the Bolshevik sympathizer and drunk soldiers began to escape from the front letting the Germans to advance.

Duma representative Mikhail Rodzyanko came up with the idea to recruit female soldiers to replace and fortify the front. In May 1917, Maria Bochkareva persuaded Russia’s new prime minister Alexander Kerensky to set a battalion of women (12). The idea was to mobilize the non-combatant alchoolic troops inspiring them by these fearless female warriors.

Despite being not accustomed to the difficulties in the military training, many women participated in this batallion for the sake of the defence of their country. The first wave of applications consisted of more than 2000 women. After the trainings and eliminations 300 women were recruited and formed the battalion.

The battalion which was named as the “1st Battalion of the death of Russian Women” was sent to the front in June 1917. On the arms of their uniforms there were the symbol of death, the Totenkopf’s picture. This symbol was before used by the Prussian army with its best-known form (13).

The drunk and sluggish male soldiers bearing the Bolshevik ribbon on their arms treated these women as if they were prostitutes (14).

The Women’s Battalion first clashed with the Germans in July 8, 1917, in Smorgon, at 750 km from Moscow, in the region of Grodno. The male soldiers getting boiled by women’s prowess began fighting too and pushed the Germans back. However their causalties were already much greater than expected in the first day. 30 were killed, 70 wounded out of 170 female warriors.

Female soldiers heroism was quickly heard all over the country and that led hundreds of more women to apply to join the army from many parts of the country. But in the face of the sheer number of causalties, Kerensky government stopped female recruitments to the army.

The Women’s Battalion’s heroism was first narrated 98 years later, by the Russian film director Dmitry Meskhiev’s film “Battalion” in 2015.

A new troop was formed then out of the soldiers Bochkareva didn’t lead to the front. This troop, led by captain Loskov, was assigned to guard the Winter Palace.

In November 7, 1917 (the new calendar) the Bolshevik Vladimir Antonov Ovseenenko and 10-12 militia entered through an open door into the Winter palace and arrested the ministers of the Provisional Government gathered in a room of the palace (15).

The ones who ordered to the female guard troop not to resist to such a couple of thugs were thus again the ministers of the Provisional Government. The reasons why the ministers ordered to the Squadron not to resist, the reasons why they connived the occupation of the Palace, whether they did this treason as against to money or for the forgiveness of their lives, are still the untrodden subjects of research for historians. This event was the coup d’etat that was made with the least people in history, which, then gave birth to a civil war that caused the death of 10 million Russians.

Among these ministers, Antonov Ovseenenko was the one who ordered the plunder of the wine cellar – a scene which was widely criticized in Sergei Eisenstein’s October film. Antonov Ovseenenko was an Ukrainian Bolshevik arrested for committing an attempt to coup d’etat against Stalin in 1938 and was shot.

Taking the advantage from not firing of the women’s guards the Bolshevik horde got easily penetrated inside the palace, threw several female soldiers down from the windows, one female soldier committed suicide, three of them were raped by the Bolsheviks (16).

In November 21, 1917, The Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee abolished the Women’s Battalion.

Sergei Eisenstein, however didn’t diffide in depicting these women soldiers as demonic lesbians. Here are the scenes in the film ‘October’ ridiculing and humiliating them:

Eisenstein first shows the mother-child statue in the Winter Palace. Then the female soldiers pretending to do some training are brought to the screen:

And here in an examplary to Eisenstein’s ‘sublime’ symbolism: the rifle’s shadow falls on the mother-baby statue:

And what do we see next: women stop pretending to do military training, they laugh, hand in hand… the camera focuses on two hands holding each others. Then they hug each others …

One’s hand holds the hip of the other:

Such scenes humiliating women used to be longer and more diverse in earlier versions of the film ‘October’ while – we believe – they were cropped to get reduced in time in order to preserve the propagated “sublime geniusness” of Eisenstein.

As we had already explained in our previous articles in detail, the currently known versions of Eisenstein’s films are far from being Eisenstein’s own products but instead are the products of a large number of staff operating behind. The name “Eisenstein” is nothing but just a label stitched on the final product.

Sergei Eisenstein as the real person, however, was the perfect obscene example for the fabrication of art and artist out of rubbish by intellectual elites. While thousands of gays and lesbians were being persecuted in forced labor camps in the Soviet Union for their unapproved sexual orientation, the world-renowned misogynist Sergei Eisenstein, famous by his homosexuality and his fake marriage with Pera Atasheva, managed to take the advantage of his unfair blessing to conduct an arrogant and nasty life profitting from all sorts of priviledges of the Bolshevik aristocracy.

* Alfonso Cuaron who came back again into question with his film ‘Roma’ (2018) last year, had also insurged against this order of fabrication of art and artist out of rubbish in an earlier period of his life with his sole masterpiece ‘Great Expectations’ (1998). Whereas in the days shortly after he received the order of the film ‘Roma’ from a – still non-disclosed – producer, he needed to define this masterpiece as his black sheep of his career. We have already discussed this dirty story of Alfonso Cuaron in our previous opus ‘The Autopsy of the Film ‘Roma’: Why did Alfonso Cuaron discredit his own masterpiece?’, in detail.

The misogyny of Eisenstein was a phenomenon which was determined before us. The director Mikhail Romm writed in his memoirs “Eisenstein was particularly keen to draw obscene pictures next to women” (17).

David Gillespie from the University of Bath, in his study titled ‘Sergei Eisenstein and the Articulation of Masculinity’ (2008) tells us that the scenes of the film ‘October’ showing female soldiers had also been criticised by the feminists of that time. Among the friendship circle of Eisenstein, Mayakovsky’s lover Lily Brik’s husband Osip Brik had complained that “the Revolution was depicted not as a historical event, but rather reduced to a battle of the sexes” in this film (18).

It has been written a stack of texts on the pathological relationship of Sergei Eisenstein with his parents and how his traumatic childhood affected to his personality and his so-called “genious” cinematography. David Gillespie’s article is one of those. These texts tend to mean a blurry link between the traumatic childhood and the artistic geniousness. Such kind of evaluations are all nonesense but intellectual masturbation, seeking to correlate the mystery of psychoanalysis to the mystery of geniousness, through their coparcenary of their mystery.

Our stance here by contrast is to fully reject any mystification of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis transformed into its most refined form by Lacan is a fully concrete and practical experience discipline to interpret and understand everyday life practices – it gives thus no way to any kind of mysticism. Additionally we already reject the concept “genius” which, since, it also evokes the concept of mystery. Let’s carefully study hereunder how a well known Eisenstein fan, Marie Seton, adorns her text using such eclectic arguments to build a rhetoric to endoctrinate the reader to Eisenstein’s geniousness – should, however, the reader manages to filter this rhetoric ornamentation, then becomes easier to see Eisenstein as the real person free of any ethical principle, an incapacitated and manipulated element staying always in service of political power.

The concurrent fabrication of the ‘genius’

Our question is how the avant-garde intellectual and art elite which, we consider as the current variant of the Mediaeval scholasticism find especially such traumatic personalities to polish and applaud as ‘genious’.

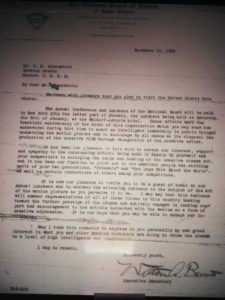

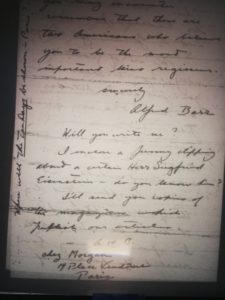

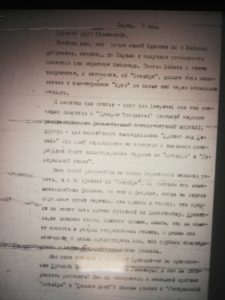

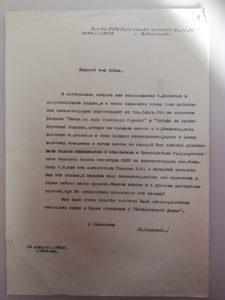

Going through the story of the film ‘October’ here we try to follow the tracks of this fabrication. The film ‘October’ had took a special attention of an important American figure right after its short-term impressions in the Soviet Union: Alfred Barr. Let’s study hereunder the letters we found in The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI) in Moscow, written by Alfred Barr (Wilton Alfred Barrett), the director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) based in New York, to Sergei Eisenstein:

Better to see here the bottom part of the same Letter:

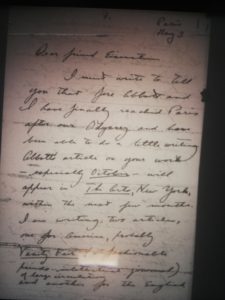

And here it is the other Letter, which is colloquial, private, handwritten, but on the same topic:

And this is its Russian translation in the same file:

Source: The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI)

The first letter exhibits the fact that in the immediate aftermath of the failed impressions in USSR, the film ‘October’ was shown in Germany and that it had also failed, getting again negative reviews in Germany.

The letter we show first is written with an official language with typewriter, thus it is formal. In this letter, Eisenstein’s previous film ‘Potemkin’ is praised with ‘October’ and both films are defined as great works of art.

The second letter is written by handwriting again by Alfred Bar on the same topic. The things that can not be expressed in the first letter as it was formal, are told in this private letter: Alfred Barr asks to Eisenstein what he thinks about the fiasco and the negative reviews for the impressions in Germany. Here we must first note that this questionning of Alfred Barr is incompatible to a regular and kind dialogue regime. Then Alfred Barr mentions that the film was too magnificient for the American public to understand it. We must also note that this statement, rather being cordial, is an implicit humiliation. This is what the American implicitly says to Eisenstein:

“You are such a big genius that no one can understand you here. But don’t worry, we will still prepare reviews and articles written for you to be published in weekly magazines to polish you and your movies!”

The above letters coincide to the beginning of the period when Eisenstein went to the 4-year long trip abroad with Stalin’s special permission. This 4-year long travel correspond to the period between ‘October’ and ‘Nevski’. During this interval he made two films (Generalnaya Linea (1928) and Que viva Mexico! (1931)) which both were fiasco and thrown to the stockroom without being shown in the cinemas. We have previously discussed the strange liaisons regarding this 4-year long trip in our main article.

After the War, the British Marie Seton publishes Eisenstein’s biography (1952). It also worth to stress here the similarity of the praising words of Marie Seton to the wordings of Alfred Barr in the letters above:

“…yet to understand Eisenstein an extensive education in the arts was necessary. With such an educational gap between Eisenstein and his audience, how was he going to fare? How was he to make himself understood ? Even Huntley Carter was conscious that the production of The Wise Man ‘went at a great speed, almost too quick for some spectators’. If this was the impression left by Eisenstein’s first independent work, what would be the general reaction to his work as it became more complex ?” (19)

The sinecure to intellectual elitism: Symbolism*

The term ‘avant-garde’ roughly designates all art movements that emerged in the second half of the 19th century which claim to be progressive and creative in developing a revolutionary world perception by rejecting classical forms and the classical art education. The term is derived from ‘vanguard’ which is originally a military term. So the ‘avant-garde’ artists attribute themselves a ‘self-sacrificial’ mission as in the military ‘vanguards’:

“So I try hard, I toil, everthing I do may go to waste … still, I sacrifice my labor, but eventually, thanks to my attempts, people’s sense of aesthetics will change the perception of the world seeding the revolution!”

As natural tribulations are thought to be the procursors to miraculous happenings, the avant-gardist too, relying on some kind of logic of revelation, they believe any change in human consciousness would lead to wonderful changes in society.

Thus, even with its most simple definition, despite their claim to be progressive, it is clear that avant-gardizm was in fact a modern kind of mysticism and bigotry. It has created its own ramified scholastic disciples: Dada; Constructivism; Suprematism; Futurism; Cubism; Theater of the Absurd; Conceptual Art; Object Oriented Ontology, Kitsch Art …. and Symbolism.

Here we will not argue, of course, that all art works related to avant-gardizm were all rubbish. These currents had created a small number of really valuable pieces that echoed public appreciation. Regardless to endless nonsensical schisms providing utensil to “Profs” lectures in art schools, we argue a basic bipartite distinction subsuming all sorts of avant-gard artworks – and we differentiate these two categories according to their approach to art education:

1) The one appropriating the classical art education, advocating to learn classical forms, then refusing them to change these forms with an attempt to capture innovation.

2) And the other which wholly rejects formalism and art education.

The first of the above categories of avant-gardizm, one can argue that, had produced some valuable art works that are still standing today.

The second category, however, is complete rubbish.

This fundamental distinction was also significative in debates on art politics during the Bolshevik Revolution until the settling of Stalin’s socialist realism. Proletkult was representing the first while Trotsky’s doctrine was advocating the second.

Now we will draw attention to the similarity between the functioning of hegemonic power and the mechanism of aesthetic perception. Let’s first recall that avant-gardizm had arisen through art-politics relationship, appropriating a vague political mission to itself. This similarity also reveals that the most dangerous and defeatist current among the avant-gard ramifications for a sound socialist project, was symbolism.

Let’s start by asking what is a ‘sign’ or a ‘symbol’.

Taking in a broad sense, the communication between people entirely operates by the transfer of ‘signs’. Language is a symbolic system – a system of signification i.e. a convention of attributing meanings to symbols. To understand the relationship between power and language, we refer to three categories constituting subjectivity in Lacanian psychoanalysis, the Symbolic (S), the Imaginary (I) and the Real (R):

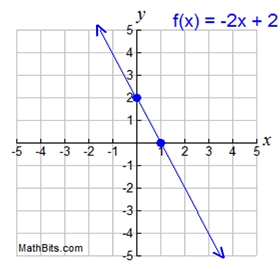

What we see above are the two different expressions of the same mathematical function (one is the numerical expression (f (x) = – 2x + 2) and the other is its description in cartesian diagram. Both are given within a proper SYMBOLIC convention to make everyone able to understand what they signify. Thus, let’s take the above statements (symbolic descriptions) as a discourse of power. Since they fit to the convention, they are prone to discussion and agreement – which we could complacently define them as ‘legitimate power’.

This time, let’s consider the representation of the same mathematical expression in the mind. This is IMAGINARY. Even if we can symbolically express (symbolize) the relationship between variables through this function, we can not capture in our mind the value of the function for infinitely differentiating values of the variables. Therefore, we resort to the help of the other symbolic expression (the Cartesian diagram), but this time we fail to construct the lengths of the axes, function curve, of both ends of the continuum to infinity, their dimensionless intersection points in REAL and so on … and:

When we push ourselves hard to imagine that impossible Real, we end up as in the visual description above: “What’s for?”

Thus, following the symbolic convention saves us not falling into such imaginary impasses. And as long as we establish contingent mathematical implications to phenomena in Real life math never deceives us. It functions in the same way for everyone. It is fair. Therefore complying to the symbolic convention and the care of justice are directly related. Political power too, it functions as a symbolic representation of a mathematical function, representing the Real that is impossible to imagine: as it loses legitimacy, it also loses its symbolic consistency (eg multiple legal systems, multiple official languages, all forms of discrimination, including the “positive” ones, etc.).

The symbolism in art too, it is located right on the opposite side of the realism in art. Having adopted the claim that the truth could only be represented – not directly but – in mediation of new symbolisations, it plays with the language. It follows the principle to disrupt symbolic conventions. That way, it generates “highly” intellectual “deeply” intriguing discourses that only understood by whom who manage to understand them. They are analogous to the scholastic Mediaeval clergy. They generate discrimination.

When we look at the etymology of the word Symbolism (syn + Ball) we find the notions of “to gather and to throw”, which is synonymous to “shit out”.

What does the symbolist obscurantist is to coupling new signified/signifier pairs – as in Saussure’s formula – and generating various associations out of these couplings – as defined in Pierce’s formula. The symbolist obscurantist offers these couplings as “art”. What they do, however, is to disrupt the commonly understandable language, opening a space to maneuver for profiting out of misunderstandings by inventing an elitist intellectual language.

* The thesis that the authority can function if and only if its limits are not imaginable due to a LACK of symbolization, belongs to Professor Zizek (20).

The phrase “How was he to make himself understood” that was used for Eisenstein, the ‘symbolist’ of the art of cinema, was indeed an intellectual sheath to hide his actual incapacity.

That same discourse of Marie Seton and Alfred Barr had then been transferred to another American in the 70s: 1922 born American intellectual and film critic Annette Michelson (1922 – 2018) presented the film ‘October’ as the masterpiece of avant-garde cinema and had contaminated the US intellectual and film circles with this idea. In 1976 she issued a cinema periodical named as “October Journal” which is still being published today (21).

Фонд Исторической Фотографии Имени Карла Буллы

(Karl Bulla Foundation and posthumous rehabilitation)

By contrast, the news and comments in the media of today’s Putin’s Russia disclose the dirty background of the film ‘October’:

In the Internet newspaper of St. Petersburg, spbdnevnik.ru, Marina Alekseeva wrote that one of Karl Karlovich Bulla‘s two sons has filmed the events on October 1917 in live and Sergei Eisenstein imitated these documentary shots in his film ‘October’ without taking Bulla’s permission, without making any reference to him, even without acknowledging him (Alekseeva, September 25, 2018). Karl Karlovich Bulla is today regarded as one of the most important photographers of Tsarist Russia (22).

This proves once again Vsevolod Pudovkin‘s statement that ” Sergei Eisenstein steals everyone’s ideas and profits out of them without neither paying any gratitude nor referring to them”.

Meanwhile, let us also note that Sergei Eisenstein was not the only thief in this market: the Soviet director Mikhail Chiaureli too, he used the images of Bulla Brothers in his 1938 film ‘The Great Blow without making any reference to Bulla.

Karl Karlovich Bulla (26 February 1855-28 November 1929) took films and photographs of the 1905-1907 Russian uprisings in the Baltic region. His sons Alexander Bulla (10 April 1881-13 March 1943) and Victor Bulla (1 August 1883-30 October 1938) also continued their father’s tradition of documenting street events and they recorded the events of 1917 too.

The Bulla archive was an unexplored archive until very recently. For this reason, the world still knows Dziga Vertov of eastern Poland as the first documentary filmmaker. Now we learn that the first documentary filmmaker was Karl Karlovich Bulla, after this archive was revealed.

Why did the Bulla archive remain hidden for so long, and why was it discovered only in the 2000s?

Father Karl Bulla handed over his famous photograph studio in St Petersburg to his two sons, Alexander and Victor Bulla. The brothers were as successful as their father. Especially Victor when he was only 19 years old (1904), he took a high risk on the front lines of the Siberian front during the RussoJapanese War. Victor Bulla was the pioneer of war correspondent. The photographs of Victor were published regularly in the magazines Нива (Niva) and Искры (Iskri – this should not be confused with the illegal Iskra newspaper published by Lenin and Parvus in the same years). The Bulla brothers shoot the 1917 events and the subsequent Civil War and street events.

In 1938, Victor Bulla was reported to be spying by one of his employees at the studio. He confessed to the crime – probably under torture. The following processes proceeded with the standard practice of the ‘Great Purge’ time: his family was informed that Victor had been a public enemy sent to a labor camp. However, instead of being sent to a labor camp, he was shot shortly after he was arrested – as was done for many. The social cost of the restoration of the state institute was very heavy. Next to the real traitors, many decent and productive people of the country were being slaughtered after show trials which don’t tolerate any slightest doubt.

After World War II, many innocent people, who were thought to be traitors in 1933 and 1938 Purges, were returned to their dignity. Victor Bulla was also found innocent in 1958 and his dignity was returned. His secret archive, however, was not disclosed until 2004, and therefore Dziga Vertov continued to be recognized as the first documentary filmmaker.

The year 2004 was again an important turning point for Russia. Putin was consolidating power, the thieves (kleptocrats) such as Boris Berezovsky, Mikhail Fridman, Vladimir Gusinsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Vladimir Potanin, Alexander Smolensky, Pyotr Aven, Vladimir Vinogradov, Vitaly Malkin, people’s marrow-suckers, were either arrested or expelled from the country. The country had re-mobilized its dynamics of economic development using its own resources and technological know-how. In this revival period, many post-humously rehabilitated names in the 1950s began to find their places they deserved in the re-writing of the Russian History.

Bulla family was one of them. In 2004, in St Petersburg, at the same address as the Studio of Karl Bulla was located in St Petersburg (54 Nevsky Prospekt) the Karl Bulla Historical Foundation of Photography and museum was founded. Here the photos and video footages of Bulla family began to be displayed. And that way, Sergei Eisenstein’s theft began to come up to the agenda.

Between November 1, 2017 to November 30, 2017, Karl Bulla Foundation had organized an exhibition for the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. While several organisations in London and the United States named as “100 years celebration” making impressions of the film ‘October’ in pumping fascination to Sergei Eisenstein, the exhibition of Karl Bulla Foundation in Russia revealed some parts of Bulla brother’s two documentaries: “The Chronicle of the Revolution in Petrograd” and “The Great Days of the Russian Revolution: February 28 – March 4, 1917” (23).

The forgotten rivals of Sergei Eisenstein

For the celebration of the 10th aniversary of October Revolution, the Bolshevik government had not ordered just one film to just Sergei Eisenstein. Besides him, much more talented film directors, Vsevolod Pudovkin , Esther Shub and Boris Barnett were also given film orders.

Vsevolod Pudovkin

Pudovkin, along with his assistant Mikhail Doller (1889-1952), shoot the film “The End of St. Petersburg” (Konets Sankt Peterburga). The screenplay was written by Nathan Zarkhi. The film was shot at the studios of Mezhrabprom in Moscow.

According to Gökhan Kuloğlu from the Institute of Social Sciences of Marmara University, Istanbul, Pudovkin was against the concept of “shooting a film”. According to him, “a film is fictionalized”. Vsevolod Pudovkin defines the art of cinema as making a fiction. Pudovkin was a student of Vladimir Gardin and Lev Kuleshov at the State Film School after the Revolution. He created his own concepts in cinema. He argued that the immersiveness of a film could only be achieved through the structuring of the details and he explained this concept of “structure” by “fiction”. Besides this, the screenwriter should take all the different situations and other technical possibilities of the camera into account, while writing the screenplay. Pudovkin described the scenario as bringing the three different dimensions together: the theme, the act and the cinematic processing of the act. According to him, the theme was a super-art concept and everything in nature could constitute the theme of the scenario. The screenwriter should demarcate it. The screenwriter had to imagine on the screen every smallest details he writes in the screenplay. The screenwriter should know how to manage the images, knowing what to choose by considering the clearest, most vibrant ones among them (24).

Sergei Eisenstein, however, as we have explaned above, in the session titled ‘The sinecure to intellectual elitism: Symbolism*’, was featuring the “symbolic fiction“.

Esther Shub

Esther (or Esfir) Shub made a trilogy with a screenplay of his own. However, among this trilogy, only the film ‘The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty’ (Padenie Dinastii Romanovykh) is known and only this film of Esther Shub was shown during the 10th anniversary celebrations. The film began with the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty’s reign in 1913 and ended with the October Revolution. The two other films of her trilogy were ‘The Great Way’ and ‘Lev Tolstoy and The Russia of Nicholas II’ (25).

The film was edited by combining the pieces of films taken during that period. Esther Shub went to Leningrad in the summer of 1926. Here, she watched a 60 thousand-meter film shot during the last Tsar and formed a 1700-meter film out of them (26).

In his film, Shub undertook a mission to justify the peace treaty of the Bolshevik government with Germany and described the cruelty of the imperialist war, the World War I. In her memoirs published with the title ‘My Life is Cinema’, Shub wrote that for this film she was helped by Vladimir Mayakovsky and Sergei Eisenstein.

In addition to showing her thankfulness to Eisenstein, Esther Shub wrote in an article that the dramatization of history distorted the facts, that Lenin should not be shown in the movies by an actor, that millions of workers and peasants shouldn’t be shown in the scenes of the Revolution and warned that, otherwise the new generation would think that the events in these days had really developed like in the film ‘October’ of Sergei Eisenstein and Grigory Alexandrov (27).

Esther Shub, who wrote these lines, has never been polished like Sergei Eisenstein.

Boris Barnet

Boris Barnet was the grandson of a grandfather who settled in Russia from England. He made a film named ‘Moscow in October’ (Moskva v Oktiabre) for the 10th anniversary of the Revolution. Boris Barnet studied architecture and painting, he worked as a stage decorator at Moscow Art Theater after the Bolshevik Revolution. He joined the Red Army and was taken back from the front because of health problems. When studying at the military school, he started boxing. He was discovered by Lev Kuleshov and he played as actor in Kuleshov’s film ‘The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks’ (Необычайные приключения мистера Веста в стране Большевиков). They then broke up with Lev Kuleshov and he began to work with Fedor Otsep. He was considered as one of the most important directors of the Soviet Union until he committed suicide in Riga in 1965 (28).

The screenplay of the film ‘Moscow in October’ was written by O. Leonidov. The film was depicting the clashes in 1917 in Moscow. ‘Moscow in October’ was frequently screened in USSR and considered as a major artpiece of “agit-prop film” (29).

Thus, what all these facts show us: In 1927, Sergei Eisenstein’s film ‘October’ was not the only film made for 10th year celebrations. Moreover, Eisenstein’s ‘October’ was the worst film among the films shot for the 10th year celebrations. It was the most unsuccessful one, among others. So why Sergei Eisenstein’s film ‘October’ was and – still now – is being presented as the sole film made for 1927 celebrations? Why did the avant-garde art museum and archive MoMA which was founded and financed by the Detroit industrialists, its director Alfred Barr and his assistant Jay Leyda, as well as the close friend of Indira Gandhi, a fellow of Indian high society and Indian political elite, the British journalist and author Marie Seton, undertake the mission to promote – in such a well organized and coordinated way – Sergei Eisenstein’s failed film as a masterpiece? Why this art market elite cared and polished just Eisenstein undermining other much more talented Soviet directors like Vsevolod Pudovkin, Esther Shub, Boris Barnet and so on?

And right here let’s ask a more disturbing question: Aleksandr Petrovich Dovzhenko is the contemporary of other directors we mentioned above. He is however a less well known, an unimportant, talentless, average director. Dovzhenko is Ukrainian origin. He received special attention from the MoMA employee Jay Leyda for his two documentaries he made during the 2nd World War, concerning Kharkov front, one depicting before the Battle of Stalingrad ‘Ukraine in Flames’ (1943 – Битва за нашу Советскую Украину) and the other after the Battle of Stalingrad ‘Victory in Right Bank Ukraine’ (1944 – Победа на Правобережной Украине).

Jay Leyda had found the negatives of these documentaries but could not have found the scripts accompanying to the images and he was in pursuit of finding them. Because he wants to organize an event to show the films of Dovzhenko in the US. For this purpose, he writes to Dovzhenko’s widow Yulia Yppolytovna Solntseva, asking these texts to be sent to him. Solntseva politely rebuffs Jay Leyda, replying “Write to Soyuzkino, ask them to send to you the scripts” (State Department of Cinematography), “but even if you write them soon, you are too late”, she says:

This correspondence was dated 1965. This is the year right following the fall of Khrushchev. Brezhnev had just come to power, so the Western world is probably again highly concerned in the trail the Soviet Union will follow. Let us remind that Khrushchev was Ukrainian. And it is precisely in this a period that Jay Leyda is commissioned to polish and promote the Ukrainian director Dovzhenko.

And let’s see now what’s happening with Dovzhenko today:

Today, the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine organizes film screenings, events, introducing Dovzhenko as the “great Ukrainian cinema genius”. After this polishing, will there be a new history writing for the 2nd World War that will clear and heroize the history of Ukraine, and fondle the national pride of Ukraine??

Footnotes:

- “It’s the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution, but Russia is getting tired of Soviet nostalgia”, South China Morning Post, 7 November 2017, www.scmp.com/news/world/russia-central-asia/article/2118749/its-100th-anniversary-october-revolution-russia

- Oliver Carroll, Russian Revolution at 100: Why the centenary means little to modern day Russia’s leaders and its people, Independent, 5 November 2017. www.independent.co.uk/news/World/europe/russia-october-revolution-100-years-bolsheviks-soviet-putin-communist-party-federation-tsars-a8038911.html

- ibid.

- The Moscow Times-3 Kasım 2017- themoscowtimes.com/articles/revolution-centenary-unearths-debate-over-lenins-corpse-59466

- Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution, 1890-1918, R. Hart-Davis Educational Publications, 1970, page 148

- For those who doesn’t know Russian, the entire book can be accessed through the following link and read using the website translator: https: //www.e-reading .club / bookreader.php / 1009748 / Heresh _-_ kuplennaya_revolyuciya._taynoe_delo_parvusa.html

- based http://www.1917.org.uk/spark-film-festival/

- Yevgeny Chernykh, October Revolution in Russia was prepared for the money of the West, Komsomolskaya Pravda, February 2, 2017 https://www.kp.ru/daily/26642.7/3661075/

- Irina Makeeva, Parliamentary Newspaper, 26 October 2018, https://www.pnp.ru/social/kak-torgovali-muzeynymi-cennostyami.html

- – Peter Bradshaw, Hallucinating history: when Stalin and Eisenstein reinvented a revolution, The Guardian, 24 Ekim 2017

– https://histrf.ru/biblioteka/b/shturm-zimniegho-byl-no-nie-kak-v-kino-kak-na-samom-dielie-viershilas-rievoliutsiia - Mos film, 27 Ocak 2018, https://www.mos.ru/news/item/35742073/

- – https://spartacus-educational.com/Wdeath.htm

-https://www.google.com/amp/s/pikabu.ru/story/zhenskiy_batalon_smerti_marii_bochkaryovoy_5289911%3fview=amp - https://hystory.mediasole.ru/istoriya_zhenskih_batalonov_smerti

- https://fr.rbth.com/histoire/80255-bataillons-mort-femmes-empire-russe-histoire

- https://pikabu.ru/story/zhenskiy_batalon_smerti_marii_bochkaryovoy_5289911

- Mauricio Borrero, Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present, Facts on Files, Inc, NY, 2004, page 168

- https://www.psyh.ru/bronenosets-ejzenshtejn/?d=2.

- David Gillespie, Sergei Eisenstein and the Articulation of Masculinity, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, Vol 42, 2008.

- Marie Seton, “Sergei M. Eisenstein”, Grove Press Inc, New York, First Evergreen Edition, 1960, s.63

- Markus Gabriel, Slavoj Zizek, “Mythology, Madness and Laughter: Subjectivity in German Idealism”, Continuum, 2009, 109

- Neil Genzlinger, The New York Times, 18 Eylül 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/18/obituaries/annette-michelson-dead.html

- – https://spbdnevnik.ru/news/2018-09-25/peterburgskie-zhurnalisty-pokazhut-film-o-karle-bulle

– 371-85-84Social@kurier.spb.ru -

– http://www.bullafond.ru/history/

– http://fb.ru/article/387301/muzey-karla-bullyi-v-sankt-peterburge-adres-chasyi-rabotyi-vyistavki-fond-istoricheskoy-fotografii-imeni-karla-bullyi

- Gökhan Kuloğlu, Prezi.com, 3 Kasım 2014, https://prezi.com/leqpvnjsuufq/vsevolod-pudovkin-ve-kuram/

- Joshua Malitsky, Screening The Past, 14 Aralık 2004, http://www. screeningthepast. com/2014/12/esfir-shub-and-the-film-factory-archive-soviet-documentary-from-1925-1928/

- http://www. peoples.ru/art/cinema/producer/shub/

- http://urokiistorii.ru/article/2822

- Giuliano Vivaldi, Boris Barnet: The Lyric Voice in Soviet Cinema, Bright Lights Film Journal, 31 July 2011, https://brightlightsfilm.com/wp-content/cache/all/boris-barnet-the-lyric-voice-in-soviet-cinema/#.W8pGJlUzaUk

- http://media-shoot. ru /publ/16-1-0-258