Istanbul Institute of

Russian and Sovietic Studies

2nd Appendix to our article “Understanding the prodigy of Sergei Eisenstein”

Marie Seton relates the depression of Eisenstein to not being able to complete Sinclair’s project in Mexico. Marie Seton’s evaluation, however, expresses only some part of the truth – the part that is compatible with the Eisenstein myth she created, making it convenient to be told to the masses. The reason why Upton Sinclair stopped the project and fired Eisenstein was the exposure of Eisenstein’s relationship with his guide. This disclosure was the last drop. Upton’s wife, Marie Craig Sinclair got off at half-cock seeing Eisenstein’s bohemian life without being able to produce any piece of viewable film having spent months for burning thousands of meters of negatives.

The film Potemkin Battleship, shot in 1925, had not attracted any public interest in Russia. Although the film was the government’s order, it was not supported by the government: it was shown in a single cinema in Moscow and for only one week. It was then thrown to the stockroom. The reason why the government – despite it was its own order – did not support the film was the result of a serial of “bad” coincidences:

The draft scenario of the Shutko + Tretyakov duo was telling about the 1905 uprisings in many aspects. However, Eisenstein and his team did not read the script before beginning the shootings. They were therefore unaware of the scale of the scenario and had no plans for the organization of the shootings. They first came to Petrograd and began shooting the protests in front of the Winter Palace. But the weather suddenly changed getting freezy cold, so they postponed the filming there and they went to Odessa for filming the parts about the ship rebellion.

Marie Seton‘s 550-page Eisenstein biography, which nine out of ten sentences consists of polished romanticised exaggerations on Eisenstein, writes that the script detailed in Odessa was the work of Eisenstein. All other sources however, falsifies Marie Seton, confirming that the latest version was written by the famous Soviet screenwriter Nina Agadzhanova Shutko. And it was only after shooting the sections on the ship uprising that the team had seen that this part was long enough to make a film and so they skipped other parts.

Then the authorities watched the film and seeing that the plot was mainly on the ship revolt, they stopped promoting the film. Because they feared that the film could recall the 1921 Kronstadt Rebellion.

With Mayakovsky‘s intervention, the negatives were then taken from the stockroom and sent to Berlin. Since the film was too awful to be shown in the West, the famous German director Piel Jutzi was commissioned to trim and reassemble the 45km negatives. He re-assembled a 1.7km viewable film. The premiere was held in Berlin in 1926 with the participation of celebrities of its time, statesmen and an international press campaign presenting the film as a great art masterpiece.

Through this Eisenstein phenomenon, which provides an excellent example of art-politics relationship, in order to figure out how this fabrication of “artwork” and “genius artist” works step by step, we have studied the western links of Sergei Eisenstein.

The first leg of our research was to examine the correspondences of Jay Leyda, who is said to be the editor of Sergei Eisenstein (but in our opinion he did more than that, even the “ghost writing” of Eisenstein) and of his director in MoMA, Alfred H.Barr Sr.. For this purpose, we have collected from The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI) at first hand, 16 fonds comprising 456 pages in total. This amount constitutes approximately 1/4th of the total documents about Jay Leyda and Alfred H.Barr Sr. that are made available in RGALI. Administrative rules limit the amount of documents that can be received from the Archive in a single visit. In our subsequent visits in upcoming months, we expect to reach all of the documents.

Who is “comrade” Jay Leyda?

Jay Leyda made his first contact with Eisenstein in 1933 and continued to keep in touch throughout Eisenstein’s life. After the death of Eisenstein in 1948, Jay Leyda continued to correspond with Pera Atasheva, the wife of Eisenstein and had managed the legacy of Eisenstein in coordination with her.

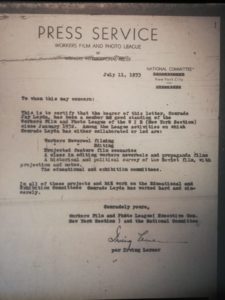

Jay Leyda applied to Eisenstein in 1933 with two reference letters. The aim of this application appears to be for working or studying as Eisenstein’s apprentice or student. One of the reference letters comes from an organization called Worker’s Film and Photo League, which claims to be founded to support workers’ movements and strikes and to raise working-class filmmakers:

In the letter we see Irving Lerner‘s signature. In his letter, Lerner, who referred to Jay Leyda as “comrade”, is known to had taught at Columbia University before the War. He then became the head of the Educational Film Institute at New York University (NYU) after the War and made documentaries for the Rockefeller Foundation. Lerner is considered to be as an important representative of avant-garde experimental cinema.

One of the works of the Worker’s Film and Photo League was shooting a documentary on Detroit Ford Massacre, which took place on March 7, 1932. At the time of this event, Diego Rivera was painting a large piece of “art”, which was then named as “The Detroit Industry Murals” with the financing of Edsel Ford. We know that Diego Rivera interfered with another worker insurrection too, called “Battle of the Overpass” in 1937, that took place during the long stay of Trotsky in their house. Diego Rivera‘s close friendships with Eisenstein, as well as with the director of MoMA, Alfred H.Barr Sr. (and also with Trotsky, for sure!) are well known facts.

The director of MoMA, Alfred H.Barr Sr. was called as “the dictator of art” during his lifetime. He used to be the authority of decision for whom will be made famous and whom will be made rubbish in the art world.

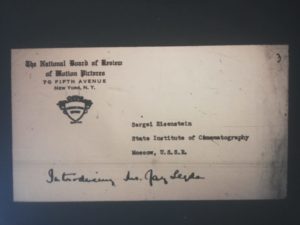

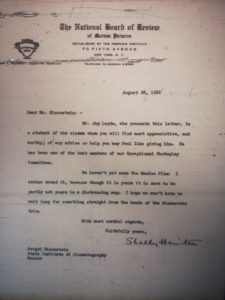

Now let’s look at Jay Leyda’s other reference letter:

This letter signed by James Shelley Hamilton, the secretary of The National Board of Review, while warranting for Jay Leyda, asks Upton Sinclair‘s Mexican film project at the end of the letter, for some reason… for – most probably – reminding Eisenstein his debacle in Mexico, where he burnt 61 km (38 miles) of negatives without being able to produce any viewable film. At the time of writing of this letter (July 1933), Eisenstein was being treated for depression in a mental hospital in Kislovodsk (a suburb of Stavropol).

Marie Seton, relates the depression of Eisenstein to not being able of completing Sinclair‘s project in Mexico. Marie Seton‘s evaluation, however, expresses only some part of the truth – the part that is compatible with the Eisenstein myth she created, making the story convenient to be told to the masses. We think that Eisenstein was closed to the hospital because his homosexuality had been revealed while he was in Mexico. Stalin’s time Soviet state used to view homosexuality as a disease. On the other hand, the reason why Upton Sinclair stopped the project and fired Eisenstein was the exposition of Eisenstein’s relationship with his guide and this disclosure was the last drop for Upton’s wife, Marie Craig Sinclair who got off at half-cock seeing Eisenstein’s bohemian life without producing any piece of viewable film having spent months in burning thousands of meters of negatives.

Let’s look at the dates of each of these two reference letters: both were written in the summer of 1933. Eisenstein and his team returned home in the spring of 1933 as ordered by a personal telegram coming from Stalin. The two major film institutions in the US, (one which is claimed to have been founded against the censorship and the other is claimed to be left-winged defending worker’s rights and strikes), immediately began seeking to send this young man next to Eisenstein – only a few months after his return to Russia. These dates mark also the beginning of the first period of terror that Stalin initiates the liquidation of Trotskyist opponents.

Hamilton included a printed page with a list of people associated with The National Board of Review. We will investigate the identities and connections of these names written here in the coming months.

A “Bezhin Meadow” quarrel?

Jay Leyda married ballerina Si-Lan Chen, the daughter of the secretary of former Chinese President Sun Yat-Sen in the following months, while staying in Russia as the “student” of Eisenstein (1934). Si-Lan Chen was a Bolshoi origin ballerina. She, however, proceded her carrier in modern dance associated with Meyerhold‘s doctrine refusing classical ballet and any kind of fomalism in performing arts.

In 1935, the shootings of “Bezhin Meadow” began. The project was the order by Stalin. The plot was like a test that measures the attachment of the team to the new agricultural collectivisation policy (Kolkhoz) of the government:

A feudal father (The Kulak) burns crops, killes farm animals, in order to avoid handing them over to co-operative (Kolkhoz). His son, a small child, denounces the father to the law enforcement officers. The father is prosecuted and sentenced in the labor camp. The uncles beat and kill the child.

Was the child a hero or a traitor? Is it permissible to delate the father and thus to betray family values for the sake of law? Does the family come first, or does the society come first?

Jay Leyda and his sister-in-law Yolanda Chen take part in the film set. According to the project, the film would actually consist of a slide show. Jay Leyda was behind the camera. However, there had happened endless debates and discussions between the director of cinematography Boris Shumyatski, screenwriter Isaak Babel and other officials. Eisenstein kept on performing his “high symbolic art” by installing religious motifs in the script. He had clashed with Shumyatski. Jay Leyda disliked Shumyatski.

By the middle of 1935, Jay Leyda resigned and returned to the United States.

In Marie Seton’s Eisenstein biography and all other secondary sources we examined, Jay Leyda’s “resignation” from the “Bezhin Meadow” project and his return home is explained by Jay Leyda’s receiving a new attractive job offer from MoMA (the so called Eisenstein’s “experts”, scholastic minded scholars copying the same story without query). The primary sources we display hereunder, however, show another story, a story showing that the foot of the goose was not as they think, that, it was different from what was supposed to be, and that it was more combed than they would think:

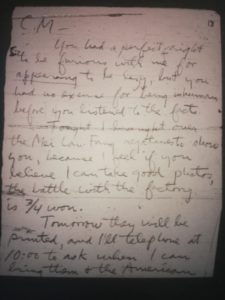

This letter shows that Jay Leyda was somehow fired and he didn’t even know why he was fired. He’s very resentful of Eisenstein. He didn’t understand why Eisenstein didn’t like his photo shoots. Let’s recall that Bezhin Meadow was an unfinished film. The project was cancelled in 1937. Shumyatski, Babel and Meyerhold were then arrested, convicted of British and Japanese espionage, and executed. Considering these subsequent developments, it would be too naïve to relate this tension that reflects to the letter above, to just technical or aesthetic matters of dispute. The project Bezhin Meadow became a test that measures the commitment of ex-Trotskyist intelligentsia and the art circles during a period which Russia was experiencing a great transformation, state’s restoration and re-establishment of food security. We, therefore, attribute this quarrel to Eisenstein’s will to keep Jay Leyda away from this ambuscade environment. It looks like that Eisenstein had fired Leyda without giving much explanation. Here is then Jay Leyda’s letter of resignation written in a more formal language:

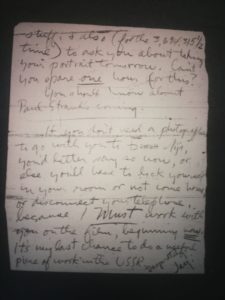

This incidence, however, had not broken Jay Leyda + Eisenstein “comradeship”. It just changed the nature of their relationship. Their rapprochement in Russia throughout the Bezhin Meadow shootings had shown the true capacity of Eisenstein to Leyda and this led to a significant change in the wording of Leyda’s future letters. Eisenstein then became Leyda’s fall guy, having known that he could not carry his undeserved reputation attributed to him, Leyda would have benefit from this reputation, by ghost-writing his books, collecting royalties… and may be doing even more. Here are some exemplary letters, which he wrote to his “teacher” after having been made home – filled with ridicule and humiliation:

He gives Eisenstein reading lists. Tells about what he had written in his name and what resources he had used to enrich the subject. He also tells about the made-up chidhood that is designed for him in MoMA, as done for all fabricated ingenuities, also giving the “good news” that visitors to the museum were already impressed by this childhood story.

Marie Seton mentions that she began meeting Eisenstein since 1934 (for the biography she published in 1960), the year when Jay Leyda was in Russia with Eisenstein. The inconsistencies in Eisenstein’s childhood story presented by Marie Seton will constitute the subject of our upcoming articles, on the basis of our investigations on Gorky, the pre-1917 Bolsheviks’ meeting on the Island of Capri, their special interest in Commedia dell’Arte, with reference to opposing conceptualisations of “carnavalesque” versus “grotesque” in the giant work of Mikhail Bakhtin.

And a last (but not a least) note: Let’s look at the names on the MoMA letterhead paper of “Comrade” Jay Leyda’s letter. We again see Edsel Ford here … and who’s more! Rockefeller, Detroit industrialists … The world is small!