Istanbul Institute of

Russian and Sovietic Studies

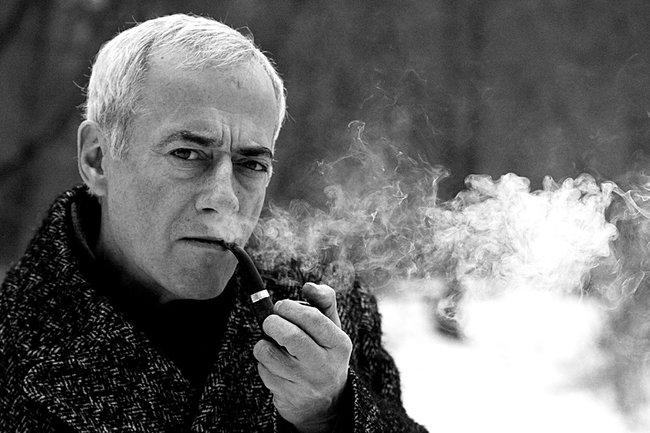

Historian Mikhail Davydov speaks on Russias ways of development prior to 1917 !

Debates about the February and October revolutions of a century ago took up all of 2017: was it possible to avoid them? Was it possible to avoid the Civil war? Why, did Russia, after overthrowing the autocracy, soon turn out to be a totalitarian country?

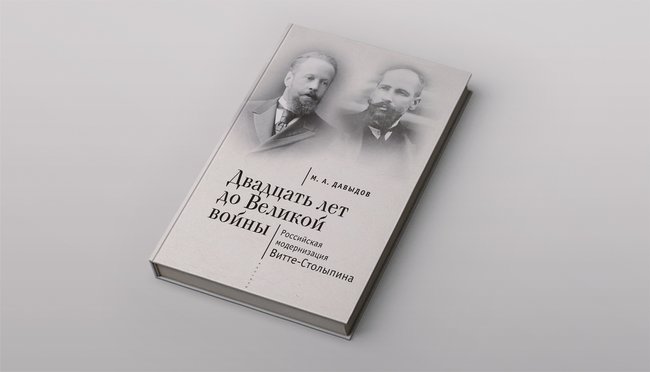

Summing up the points of this discussion, “Medusa” spoke to professor Mikhail Davydov, historian at the School of History School of Economics who in November became the winner of the Yegor Gaidar Award for the book “Twenty years before the Great War. Russian modernization Witte – Stolypin.”

Translated and edited by:

and

For Istanbul Institute of Russian and Sovietic Studies

– Is it possible to account for the spike in interest towards life in Russia at the beginning of the XX century with something other than the anniversary of the revolution?

– I am not sure there would be any deeper motives. As far as I can remember, this topic has always been popular. At a certain point, I stopped telling my train companions that I was a historian (and I travel a lot) so that I wouldnt have to explain: “So, why was there a revolution?” And I stopped because people need simple answers to very complex questions. This topic always preoccupied people, and there is nothing strange here. 1917 is something that changed the face of the world forever. Now, regarding the last 25 years in the scientific revolution many new sources have been introduced and new information, and a sort of rethinking began – but was all this really necessary, and to what extent was justified? And was everything really that bad in tsarist Russia?

Revolutionaries in Petrograd, 1917

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

– How did the impression that everything was bad in tsarist Russia get instilled?

– Excellent question, worth a minimum of two or three theses. In a sense – that is the key to any discussion of Russia after 1861. And it wasnt seriously discussed in the academic circle – we are only talking generally about decades and segments.

The repulsive image of imperial Russia, a metaphor which I have always considered a picture of Repin’s “Barge Haulers on the Volga” – is the product of mainly populist journalism, which was seriously supported by fiction. The Bolsheviks, of course, used all of these approaches, supplemented and corrected them.

Any unbiased person, seriously immersed in sources cannot disagree with the fact that until 1917 the government was to blame for everything, except for the confluence, so to speak, of the Volga to the Caspian Sea. What is the source of this presumption of guilt on the governments part, which runs throughout the entire period?

Its as if Alexander II, among other things, apologized for the past by way of great reforms. The apologies were not accepted by all. In addition, the reign of Nicholas I capitally undermined the credibility of the government in general. After 1861, society was in a sense taking revenge on the State as if to make it pay for the previous century of feudal history, for which Alexander II was not directly responsible.

Maklakov has a very strong idea. Radical reforms, like great ones, are dangerous because people expect more than the reforms can give. All that has been restrained, suppressed by power now comes out. And when the son of Nicholas I started the era of reform, all the anger that had accumulated against the policies of his father, has resulted, in particular, in the revolutionary aspirations.

Leftist populists (Herzen, Chernyshevsky, and their students), who were the most active part of society, were the first after 1861 to play a classic “Karpman triangle.” The people were appointed as victims,” the autocracy along with the landed nobility and bourgeoisie — as “persecutors” , while they theselves took on the role of “saviors.”

As “professional fighters against human suffering” (apparently, this type of official occupation appeared in the XIX century) they would not have been satisfied by any reforms in this case – what they were really after was power. And they were the ones to set the tone in the mass-media. And in the struggle with the government all means were appropriate, including explosives. At the same time, most of the nobility were offended by the way the reforms were carried out in 1861. They wanted to be in Parliament as a means of compensation.

However, all of this is part of a broader problem related to the fact that we do not understand the people of that era. We automatically project ourselves at that time and put ourselves in their shoes at the time. But for this, most of us do not have sufficient understanding of this time, there isnt sufficient amount of knowledge.

It would be an act of misinterpretation to consider people in the mid XIX century as “rational autonomous individuals,” as the classical definition of the modernization goals would have it – they had yet to become such individuals. That is, one should not identify people at that time with us, as contemporary people transported 150 years ago.

Lordly entrance hall and lordly human, no matter what (even in the Winter Palace) is a lousy school of morality. Therein originated, in my opinion, the disgusting double standard of Russian society, when the king and his officials can be killed (and many believe that it must be done!) because of alleged predatory reform, while punishment for the killers of the government is not mandatory.

[Sergei] Solovyovs thought explains a lot. He says that everyone, starting with the new emperor and his family, sas the desire to break away from Nicholass prison, but the prison does not educate people for freedom, and so it was easy to imagine “how people released from prison into the world will play tricks, how many people will be fainting unaccustomed to the fresh air.”

They had to flee from the prison, cursing it, so it is not surprising that the press began swearing, denunciation, and denial. But the problem of creation remained in the shadows somehow, and it was not clear what would replace the order to be destroyed.

Gaining freedom of speech and real civil rights, unthinkable before the reign of Alexander II would make society “normal.” It did not.

In 1861, the year of the liberation of the peasants, the students were on strike, proclamations calling for the murder of the royal family were heard in Petrograd.

Picture from the personal archives of Mikhail Davydov

– Was it not the government that provided reason for this?

– What was the reason? The fact that 23 million people were released to freedom? And then, what does it means – it gave reason? If you do not like something, you have to throw a bomb at once?

At the same time, naturally, I’m not saying that the government was “white and fluffy”. It was not. But my problem is not distribution, relatively speaking, of guilt. We need to understand and explain this. And then there’s a lot of work to be done.

– The main plot of your book – a myth about the failure of modernization Witte – Stolypin. Can you explain what this modernization was?

– Cars and phones were then still delights of civilization, but modernization has created conditions in order for these things to become commonplace in the not too distant future. The essence of the Witte – Stolypin modernization consisted primarily in the expansion of the area of freedom of the countrys population, that is in the future development of potential of the Great Reforms. Russia conducted a successful start in industrialization and agrarian reform, based on a provision of 100 million Russian peasants with full civil rights; the scale of the reform did not have precedent in world history. As a result, at the end of XIX – early XX century, Russia has become one of the fastest developing countries in the world, which had the highest average annual growth rate of industrial development (6.65%, according to Paul Gregory ).

The growth of the level of population freedom, the expansion of the means of its self-realization, and the increase of the number of life scenarios accessible to ordinary people was eventually reflected in the rise of their welfare, which is confirmed by a variety of statistical sources. The processed results from these sources are presented in my book.

Stanislaw Jerzy Lec expressed a thought that is very pertinent here: toppling monuments leave the pedestals – they might always come in handy. So, I’m not going to substitute one myth with another and I do not say that everything was great in Tsarist Russia.

I’m just pointing out that it was not as bad as we have been assured for decades that it was and that by extending the scope of the rights and freedom of people, they were living better, that Russia was on the rise. The revolutions of the early twentieth century are misinterpreted as “food riots,” as a result of the disturbance of the people, driven to despair by their hopeless situation.

I was able to show and prove the failure of a number of old stamps in traditional historiography. Thus, the thesis of the “hungry exported” bread is not confirmed by the statistics of production, transport and disposal. The idea of the growth of arrears since 1861 as an objective indicator of the worsened standard of living of the peasants also failed verification. The Stolypin agrarian reform was by no means a “failure,”quite the contrary.

The book explores the problem of “semantic inflation,” which directly affects our understanding of the past. It is clear that in the late XIX- early XX century the concept of “hunger,” “need,” “back-breaking fees,” “violence,” “arbitrary”, which have always formed a negative image of pre-revolutionary Russia, were not invested with todays meaning. The semantics of these terms has changed because life itself changed.

Over a hundred years after, Stolypin’s agrarian reform was considered to be synonymous with tyranny and violence. We may accept that idea. And then what was collectivization?

Then what words will we find in Russian to characterize the collective farm village with the law on the three spikelets, which provided for two penalties – 10 years and execution?

“Hunger” is another relevant term. With the exception of the deadly famine of 1891-1892 when most of the victims died of cholera (the treatment was not known back then), before the revolution, the word “hunger” meant crop failure, in which case the government provided assistance to the affected. Only in 1891-1892, this assistance was over 160 million rubles (about 7.7% of the imperial budget). In 1891-1908, food aid cost the treasury about 500 million rubles. I also mention that the “Big naval program,” which by 1930 had to give Russia a modern fleet, was worth 430 million. The government of the empire never left the people to fend for themselves.

Our current ideas about famine are derived from the historical experience of the Soviet era, and it was fundamentally different and infinitely more tragic. Famine in Soviet times means mortal hunger and cannibalism, and except for the years 1921-1922, no food aid was given by authorities. But we continue to use the same word, “hunger,” to refer to a poor harvest with “royal rations,” the tragedy of 1921-1922, the Holodomor of 1932-1933, the starvation of besieged Leningrad, and the famine of 1946-1947.

This semantic inflation largely determines our current perception of imperial Russia as a poverty-stricken backward country, and this situation must be addressed, otherwise we will remain prisoners of the mythology of the “Short Course History of the CPSU (b).”

The fact that in the late XIX – early XX century Russia was not just on the rise – it has entered into a new, rising period of its history, is extremely important. Firstly, it counters that untenable idea that the roots of the revolution are in the impoverishment of the masses, in the worsening situation of the population during the prewar period. Secondly, the fact that the positive development of the modernization of Witte – Stolypin means that Russia has been able to successfully move toward building a state of law and a full-fledged civil society. Yes, this path would have been long and difficult, but not impossible. And certainly no more difficult than the path of “building socialism in one country.”

Peter Stolypin (third from left) during a visit of a farming hamlet not far from Moscow, in 1910

TASS

– The book is constantly repeating the formula “statistics against journalism.” How does it work ?

– For example, journalism says that the people are undernourished and starving, while statistics show that in 1904-1906, the residents of only twelve provinces out of 90 – despite the fact that for most of them both years yielded poor harvests – drank vodka in excess of the cost of the Baltic and Pacific fleet ships, lost by Russia in Russian-Japanese war. Then I have the right to question the thesis of starvation and malnutrition. If the statistics makes it clear that in the years 1894-1913 the average annual increase of the drinking income was 1.7 times higher than the average annual increase in the value of all grain exports, while the drinking and the amount of income for this period exceeded the value of total exports of bread by 13.5%, I again start thinking that journalism just messes with my head. Because during the Holodomor and the siege of Leningrad people did not have the choice between food and alcohol.

You can talk about the impoverishment of the masses in the late XIX – early XX century, but statistics show that the population of the country in the years between 1896-1913 increased 1.4 times, the number of savings banks increased by 2.2 times, the number of books and the amount of deposits on them increased 4.3 times (among the peasants – seven).

– Why Soviet historians did not like Stolypin is more or less clear, but why was he disliked by his contemporaries him from the beginning?

– Briefly speaking, I see four main points, although in fact they are even more.

First. By leveling the civil rights of peasants with the rest of the population, he struck all the supporters of the community. They were able to choose their own way of life, including becoming owners of their plots. The programs of the vast majority of the parties proceeded from the presence of the communal system, that is, from the civil inequality of peasants. Now the government is no longer artificially supporting the community, and it began to fall apart.

Second. He beat opponents with their own weapons. In his famous speech at the opening of the Duma II March 6, 1907, he outlined a powerful system of liberal reforms that have touched almost all aspects of national life. In scale and scope, they almost surpassed the Great Reforms and definitely had their logical and historical implication. Thanks to Stolypin it became clear that the concepts of “imperial government” and “civilized approach” (in the sense of Cadet) are quite compatible. And the opponents felt cheated! All this time they talked about a rule of law, and now…

Third. He was a personality and not a weather vane. Here is a remark by one of his contemporaries: “And there came Stolypin … He was a giant among the Lilliputians.” Largely it was the envy of Duma members, who, believing that they were someone suddenly faced a newcomer, who was stronger. Someone who knew how to speak clearly about his feelings, who may protect the position of the government and state values from the perspective of an objective of common sense and normal intelligible words and actions.

And finally, the notorious “Stolypin neckties”; for this vile wit Rodichev should burn in hell. He refused the duel with Stolypin, and later with Gurko.

I consider this is one of the most disgusting scenes. To discuss in detail the alleged sensitivity of the educated people is quite disgusting. Because they strangely did not spare the Red Terror victims. Let me remind you that the Cadets for the whole revolution of 1905-1907 did not condemn the Red Terror, but they constantly denounced the self-defense of the government (only here they can be considered liberals!).

Perhaps here in the clearest form the double morality of contemporary society manifested itself, in which Jewish pogroms are condemned, and agrarian ones are called “illuminations”; Red terror is justified and White is not. Incidentally, such a big humanist of the twentieth century, as Leon Trotsky, on the death of Stolypin responded with an article entitled “Bloodthirsty and dishonest!” Rather symptomatic, dont you think?

I apologize for the banality, but there are no good pogroms and there is no good terror. However, not everyone understands it at the beginning of the 21st century.

– So it may be fairly easy, particularly for the current government, to justify the logic: if we make an important reform and the liberal press and the opposition are dissatisfied, it is necessary to slightly tighten the screws.

– Power manages the tightening of the screws perfectly well without people like me. And then, show me the important reforms?! Where are they? What? So many missed opportunities over the years that it would be desirable to howl! How much can be done!

– And yet, although you write that the 150th anniversary of the birth of Stolypin caused a touching unity of the hostile forces, as his death, he apparently is now quite popular. A monument is erected where Putin, and after him Kudrin contributed.

– Again, it is necessary to clarify – he is popular in narrow circles. You cannot imagine how much dirt is directed toward Stolypin (and of course, me too) in the comments after my performances and texts!

Russia has succeeded far more in reproaching Stolypin during the last hundred years than in the construction of the rule of law, of which he dreamed and declared as the goal of his reforms.

As for the monument … It is the feature of authorities to privatize everything that, in their opinion, favors them, that can improve their image by association. Secondly, a truly great personality accommodates so much that everyone can choose what is close to him. Do they remember that? “You need great upheavals, we need a great Russia.” This is what they take out of Stolypin, and they are certainly right.

I am, too, for the “great Russia”, but only in the sense of Stolypin. After all, he, like Witte, saw the great Russia differently than their opponents, namely, a state of law, a country where people have real rights, where they have a full opportunity for self-realization, where the government is not the enemy, but an ally of its citizens. And, of course, a country corresponding to their great history, who knows how to stand up for herself and defend the others. There is not the slightest contradiction in all this.

Witte always said, you cannot pursue a policy of the Middle Ages in the 19th and early 20th century.

Prayer before the departure in 1400 of Poltava peasant walkers in Tobolsk and Orenburg province, 1908

I. Chmielewski / Wikimedia Commons

– Was society ready for a change to a greater extent than it is now?

– The question is what constitutes a society, and what changes mean.

People were more ready – this shows the whole course of transformation. Millions of farmers voted for the reform for land management, millions purchased tithes from Farmers Bank at preferential prices, the relocation of an entire province in the Asian part of Russia, the unprecedented growth and even a burst of cooperation are all indicators. Another life has started for the people.

I expressed the fact that I started to study Agrarian Reform statistics due to my desire to find out, to understand whether our people are capable of change. So, at least a hundred years ago, Russian citizens were able to change for the better.

I was never comfortable with the sayings: Russians are slaves, loafers and the list goes on, because I know where the root of the complaints about the peasants laziness and poor quality of work was. Serfdom, as well as any forced labor is in principle a bad school of labor enthusiasm. An egalitarian community reformatted in 1861 has created for its members the position of the tenant in the dorm – who would do the renovation in the room, knowing that at any moment it may be taken by someone else?

The reform has shown that once a person realizes that he does not live in a hostel, nor in the barracks, and that he was at home, that it was his own land, he begins to work differently, and his self-esteem wakes up, and more.

A society … We have a different experience – we are older. Not to say that we are wiser, but older, exactly one hundred terrible years older. We are also broken, but differently.

So now I am more pessimistic. There is, however, reason for optimism – that nobody knows the future. Where, for example, in Russia, where the word “court” was worse that a curse, suddenly there is a fair trial under Alexander II? Where did these people come from? Moreover, they had government support.

– Why, then, did these people participate in, or at least accepted the February revolution?

– Let’s start with the fact that the people was not very consulted, but more faced with the fact in 1917. Many officers were talking about the abdication of the emperor as if a squadron passed.

People in this area are generally not very logical and one-dimensional. In 1762, after the Manifesto of noble liberty, the Senate was going to erect a golden monument to Peter III, and it was toppled over four months later, and, except for the Lieutenant Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov, no one said anything.

Now, specifically in our case.

Firstly, we confuse the issue of successful modernization, the problem of removal from power of Nicholas II and the possibility to arrange the problem of unpunished looting, “redistribution”.

The overthrow of tsarism took place not on the basis of its economic policy, but primarily because of its alleged inability to successfully wage war. This is somehow overlooked when discussing the issue.

Secondly, the tzar annoyed, to put it in simple words, a large and significant part of the society. The entire affair with his wife and Rasputin becoming public so that it was discussed even by soldiers in the trenches, it damaged without precedent the prestige of the monarchy, first of all among the educated people. And it simply does not matter that in reality the influence of the Queen and Rasputin was far less important than it was thought. People believed what they wanted to believe – the supremacy of the “dark forces”. It was not so simple to recognize the true reasons for the defeat; it was easier to blame it on someone else.

Thirdly , there is an important psychological moment, which we almost do not take into account. The mass character of the Revolution, especially noticeable from the beginning of the agrarian revolution, and the Civil War – from Vladivostok to the Baltic states and Bessarabia – as it were, by themselves imply the existence of some global scale reasons able to stir up 150 million people.

There are always reasons and reasons for discontent and there are always dissatisfied people everywhere throughout the history. These reasons are awaiting to be actualized by something at a certain point. The question is what suddenly puts them into action. Why only yesterday a more or less stable society – and Russia, as well as other countries in war was more or less stable despite the war – suddenly becomes an arena of fierce struggle?

People are at great pains to realize that huge events, overturning the country’s life, and this case of humanity and planet may be the result of actions of a few specific people (the final decision about the beginning of the same World War I was taken by a maximum of 10 people), which is not allegedly the Logic of History, and the chain of cause and effect are often (but not always, of course), which involve millions of people in the end, may in some sense be described by the poem “Because there was no nail in the forge.” Avalanches and rock slide may begin with a shout or a shot, with small stones, because the small stone, moving, breaks the status quo, and then everything rolls.

The conspiracy of Guchkov was a success, but the forces were not calculated. This is a big and very sad lesson for all of us about how people consider themselves smarter than they actually were on the spot. Few people understood what abdication actually involved, such is the former head of the Moscow Police Department Sergey Zubatov, who learning of the tzars abdication, shot himself.

For the peasants, the tzar, in spite of everything, was still an utterly sacred figure. But his renunciation gave farmers a moral sanction for general redistribution. Under those specific circumstances — to unpunished looting.

– In connection with the above aspects, there is a problem of the system of liberalism. For example, if you were Witte, you would have gone to the government, if there would be only policemen Trepov and Plehve, would you have worked with them?

– Well, Witte and Pleve worked together in the government, although it wasnt a very fruitful collaboration. And this is, of course, not about me.

The opposition may be responsible and irresponsible. Responsible opposition would go to the government of Stolypin, while the irresponsible would not. And before Stolypin Witte tried to talk with the public, and it was also unsuccessful.

About the system of liberalism. What distinguishes a liberal from a non-liberal? Liberal will never throw a bomb. But the same Cadets recognized that as a possibility. Pyotr Struve wrote in one of the first issues of the journal “Liberation: we will not be hypocritical, and let’s face it the act of March 1, 1881, that is, the murder of the Emperor Alexander II of, was made by holy people. And it’s not a boy we are talking about, but one of the masters of thought, one of those who shaped the face of the party. We talked about Cadets attitude toward Red Terror.

The book of Historian Mikhail Davydov

– In the book you draw parallels with perestroika. After it, in contrast to the situation of 1917, there were no repressions against the leaders of the Soviet regime. Do you consider this way more correct than at least the organization of the State Commission for the Investigation of the Crimes of tsarist or Soviet power ?

– Everything depends on time and place. That commission, by the way, has not found anything relevant. As for the crimes of the Soviet regime, in our conditions, it was impossible. And here we are again faced with double standard, inherited by us as a legacy from pre-revolutionary times.

If our society widely recognized a system of moral and ethical values, it would be possible to think about it seriously. But there is no trace of such a system – the society is disintegrated, split morally and ideologically. We have countless streets and monuments of Lenin and other communist leaders, we are again talking about the monument to Dzerzhinsky.

Let me remind you that according to the forecasts of Mendeleev , who took in 1906 the average annual population growth rate of 1.5%, in 1950 in Russia should have been 282.7 million people and in 2000 – 594.3 million.

Based on the fact that in the 1900-1912 the empire’s population grew by 26.7%, Terry concluded in 1914 that if this pace is respected in the future, the population of Russia will amount to 343.9 million people in 1948.

At the beginning of 1951, in the Soviet Union were 182.3 million people.

Do I have to ask why our country lacked a hundred million people taking into account Mendeleevs relatively cautious outlook? In 1942 in Moscow, Stalin told Churchill that collectivization cost 10 million lives.

If we imagine that these people would stood along the railroad and joined their hands, and for each person there would be no more than a meter, then one million dead would cover thousands of kilometers. Thus, a continuous chain of victims of collectivization would cover the distance from Minsk to Vladivostok … But now we are witnessing a new outburst of love for Stalin.

What else could we say?

– In the anniversary year, even those who are not particularly interested in the history of the last century, had the opportunity to think about it, because this topic has become fashionable. Even if direct analogies are pointless, what can we understand better about ourselves today, studying the tsarist and revolutionary Russia?

– You are right, direct analogy does not work, and thank God! At least because there are no armed people, no 10 million armed soldiers who had organized Pugachevshchina with guns and machine guns “Maxim” and “Lewis”.

As for the second part of the question, it seems to me that it is always useful to know more about the past, because it offers us profundity. Thinking is always helpful. It is possible to perceive history like a casual visitor sees the museum going from one amusing showcases or picture to the next. But when you already know something, this is different because you’re different.

– With all the abundance of dry statistics, your book is anything but devoid of emotion. How was your personal attitude toward Stolypin formed?

– When I was in graduate school, a wonderful historian Cornelius F. Shatsillo told me how Stolypin behaved in 1905, during the revolution, how he was not afraid of anything or anyone. And when I started to read more on the subject, I realized that I was dealing with a noble descendant of a noble family. It is clear that human and professional attitude are two different things, but personal respect has always been present.

However, I do not believe that Stolypin as a statesman was flawless; in my opinion, there are no such people in history.

– It is significant that two of your main characters, Witte and Stolypin strongly disliked each other. Have you managed to convince at least one of your opponents, who believe that the modernization of Witte – Stolypin was useless?

– For me the relationship of Stolypin and Witte is the subject of some sadness because I respect both of them. Wittes hatred for Stolypin is a trivial jealousy, because Stolypin essentially implemented ideas that Witte had worked on for years. Witte was hurt. Actually, I’m not sure that Witte had Stolypins will.

I am well aware that my opponents will never agree to my ideas, and I do not want to negotiate with them on the matter. They have absorbed firmly the idea of impoverished tsarist Russia, and if a man wrote all his life that Russia was backward and that true industrialization was made by Comrade Stalin, no other data would change it.

But some people whose opinion matters to me, I managed to convince. And not only one – unless, of course, they are deceitful.

Andrew Borzenko