Istanbul Institute of

Russian and Sovietic Studies

Note: This study is being elaborated by revisions and appendixes. The Log of revisions is located at then end of the article.

Known for his leftist identity, Ken Livingston’s victory in London municipal elections in 2000 created excitement in the left circles in the UK as well as around the world. One detail that escaped from the eyes was that Ken Livingston participated the municipal elections as an independent candidate from the party, even though he was a member of the Labor Party. Simple tactical explanations were invented to explain this strangeness. We can, however, try to better understand this tactical choice through Eisenstein’s story we present below, within the framework of deep decomposition on the left, whose roots go back to 1908 and 1916.

Despite this individual outflow in 2000, Ken Livingston’s Labor Party membership continued until 2018.

Ken Livingston is a politician known for his hardworking and challenging personality. He is also known as one of the predominent figures in the Labor Party. In 2004, in collaboration with the Contemporary Art Institute of London, he intended to organize a magnificent outdoor show for the Potemkin Battleship film. Pet Shop Boys was ordered to compose the music for this show. Pet Shop Boys is also a pop group known for its leftist identity. The gathering and restoring of the negatives required an extraordinary international intelligentsia mobilization. Let’s look at the actors of this campaign and the story of the restoration of the negatives of the film:

The 30-meter portion of the negatives was missing due to censorships. During the Second World War and the Cold War, the negatives remained in storage for many years, all truncated, shattered. The film was previously shown in Moscow by Gosfilmofond of the Russian Ministry of Culture in 1966. Different versions had also been shown in Europe in the 50s and 60s. But none of these versions were complete and clean. There were censorship differences from one version to another.

It is for this reason that film historian and collector Enno Patalas comes to scene for Livingston’s Trafalgar project. Enno Patalas who used to work as the director of the Munich Film Museum, wrote this restoration story of the negatives in 2005 in the Journal of Film Preservation magazine. When we throw his fancy drama expressions away to make a clean reading of this article, we see that the final form of the movie shown in Trafalgar was a bundled patchwork of a large team work rather than the product of a “genius” film director. Anna Bohn, assistant of Enno Patalas, supplies a negative relatively in good condition from the archive of her boss and combining them with other fragmentary parts by the cooperation of experts from Deutsche Kinemathek and Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv (Berlin), Gosfilmofond (Moscow). Gosfilmofond’s then director Naum Kleiman is an Eisenstein fan. Below we will refer again to this important name.

The three big street parties and Berlinale

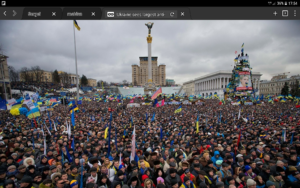

Now let’s open a short paranthesis here. Hereunder we see the protests in Tibilisi Liberty Square, the mass protests under the blue-and-white NATO flags symbolising the world peace:

Ken Livingston’s show took place on 12 September 2004 at Trafalgar Square. According to the English media, 25,000 people attended the event but the music of the film created disappointment. But here too, the blue-and-white umbrella symbolising peace and unity in the picture below is a detail that draws our attention. The picture is taken from Arizona-based openculture.com website:

Now, let’s look at the almost same decoration in the pro-EU demostrations in Kiev, Maidan Square. Again a similar tower at the back and again the blue-and-white EU flags symbolizing peace and union:

The so-called “Rose Revolution” in Tibilisi took place just a few months before the Trafalgar show. The so-called “Orange Revolution” in Maidan began just two months after the Trafalgar show, that is, the end of 2004 (The pictures above are taken from 2008 Tibilisi and 2013 Maidan protests, since we couldn’t find in the web the same angle photos from 2004 protests, but we know that both events occured in the same squares and that an “occupy square” trend had begun in the following years). Leaving plenty of huge parks in London aside, the Major Ken Livingston preferred to organise the event in the central square of the city where the principle arteries connect – troubling the whole transportation network. What is important for us here is the similarity in the use of flags that symbolize the economic and military hegemony of the West together with the tower decor, in all three events. Seeing all these contingencies, it becomes possible to us to think that an event that was presented as an “art event” was in fact designed in a way to create suitable reflexes to imperialist politics in mass perception.

After Ken Livingston’s show in Trafalgar, the film was then shown the following year at the 55th Berlin Film Festival (Berlinale) just the following year, this time for the 100th anniversary of the 1905 Uprisings. In Berlinale however, the Pet Shop Boys’ music was replaced with the original music of Austrian composer Edmund Meisel. For some reason the press had reported that the shows in Berlinale which were attenden by few hundreds audiences were “much more successful” than the show in Trafalgar watched by 25,000 people. The reason for this assertion was expressed so that the original music was used in the Berlin Festival screening.

The order given to Pet Shop Boys also encouraged other composers. American composer Yachi Durant in 2005 and famous film musician Michael Nyman in 2011, composed their musics for Potemkin Battleship.

The story of the film Potemkin Battleship

Now let us go a century back. Sergei Eisenstein was born in 1898 in the city of Riga , then within the borders of the Russian Empire (now Latvia). He had a very traumatic relationship with his parents. The translation of his memoirs into English was first published in 1980 under the heading “Immoral Memories: An Autobiography”. Besides, Marie Seton‘s biography of Eisenstein is also an important source. However, contrary to the general tendency of scholars writing on this matter, it is not what she wrote in this biography but it is Marie Seton herself, as person, is much more interesting to us to investigate. Let’s first give a random example of her over-enthusiastic expressions in her book:

“yet to understand Eisenstein an extensive education in the arts was necessary. With such an educational gap between Eisenstein and his audience, how was he going to fare? How was he to make himself understood ? Even Huntley Carter was conscious that the production of The Wise Man ‘went at a great speed, almost too quick for some spectators’. If this was the impression left by Eisenstein’s first independent work, what would be the general reaction to his work as it became more complex ?” (footnote 1)

Marie Seton (there is no information on where she was born but most probably in Britain, in 1910 – died in 1985) had a special interest in India. In the 1960s and 1970s, she lived in India and became close friend to Indian Prime Minister Nehru and his surrounding, as well as Indira Gandhi and the Indian political elite.

In 1920, Eisenstein began his career as a stage decorator for Alexander Bogdanov‘s Proletkult theater in Moscow. There are controversial claims that he studied engineering for a year and a half during civil war years. Alexander Bogdanov, the boss and the founder of Proletkult, was however a dedicated socialist and a very well educated high profile intellectual having interests in a broad range of topics from medicine to engineering.

In 1916, the dark and the dirty year of Bolsheviks Alexander Bogdanov took position in the opposite front of Lenin. Bogdanov supported Robert Grimm while Lenin was sabotating the Grimm Peace Plan, fabricating fake imperialism theories under the service of Alexander Keskuela + Rosa Luxemburg + Karl Liebknecht.

When it comes to the 1920s, Lenin stopped supporting Proletkult theaters. Pravda initiated a negative propaganda campagne against Proletkult. Sergei Eisenstein resigned with the predicate that he had disputes with his director Valerian Pletnev (a Menshevik origin revolutionary). Proletkult was then closed in the following period and Alexander Bogdanov had been erased from history. It is controversial whether Bogdanov was the victim of an assasination or whether he died while doing medical experiments on his own.

In her 505-page brick-like book Marie Seton mentions Proletkult theaters in 16 pages and Alexander Bogdanov in 4 pages. But she doesn’t put any word on Bogdanov X Lenin conflict. Why did Eisenstein resign from Proletkult? Was he warned that Proletkult would have soon be targetted by the Bolshevic gang? Marie Seton, while representing the days of Proletkult of Eisenstein as “the apprenticeship period of a genious artist far ahead of his time” why does she depict Bogdanov and the Proletkult as elements that has not caused any conflict or trouble in the Bolshevik project?

Let’s go on: Assembly and editing techniques in Soviet cinema began with Lev Kuleshov in 1924. The fact that not Sergei Eisenstein but Lev Kuleshov was the father of assembly has been accepted since the last 10-15 years. This technique continued until 1930. Eisenstein entered Goskino (Госкино, Государственный комитет по кинематографии СССР – State Cinematography Committee) for a part time job begining cut-and-paste work in the censorship department as the assistant of Esther Shub. In this period he censored and edited many films including Mabuse of Fritz Lang and Carmen of Charlie Chaplin.

These assembly techniques allowed to extend movies to sufficient length using less footage in those times where the raw film was scarce, allowing scenes lasting 1 minute in normal flow to be extended for up to 5 minutes.

Let’s look at the story of the film Potemkin Battleship: The film is not figured and written by Sergei Eisenstein. Boris Mikhin, director of Goskino, launched a 7-film project named “Towards Proletarian Dictatorship”. This project was given to Eisenstein. He joined with Grigory Alexandrov, whom he knows from Proletkult days. They then shoot the first part or the serial named “Strike”. The viewing of “Strike” took place in 1925 and it resulted in a fiasco.

Despite this unsuccessfulness, the second film titled “1905 Protests” was also ordered to Eisentein and Grigory Alexandrov. “1905 Protests” was planned as six episodes. The scenario included the Russo-Japanese War. The two famous film screenwriters, Nina Agadzhanova Shutko and Sergei Mikhailovich Tretyakov, had written the scenario. It is questionable, which contribution Sergei Eisenstein added to the screenwriting. Sergei’s contribution is said to be some details such as the baby carriage on the stairs, and the old woman… The director of photography was Eduard Kazimirovich Tisse and the cameraman was Vladimir Popov. It is also questionable what Eisenstein was doing on the set, as Grigory Alexandrov was also the co-director.

In order to shoot the scenes of the tread to Winter Palace, the team had first planned to go to Petrograd. They however coincided to an extremely cold weather of 1925 winter and therefore they changed their way to Odessa to shoot first the session on Potemkin rebellion (footnote 2). The work starts … and it was only then after that it was seen these sections on the ship revolt were too long! So, they did not have to go back to Petrograd again as this story on ship revolt had alone filled enough time to make a film. The staff had no any serious plan, program, at hand. Their work proceded in its most disorganised way. The transformation of this patchwork by a serious teamwork into a “project” was later.

The events exhibited at the one-minute Stairs scene stretched to six minutes by assembly art do not match the real events happened in Odessa in 1905. There had been no incidents on those Stairs. The people of Odessa were not involved in the rebellion. There were limited fights and deaths during the confrontation of the rebels with soldiers and the fight had just occured within the boundaries of the port which is separated by walls and wire frames from the public areas of the city.

These staircases, formerly called “Primorsky Stairs“, were renamed as “Potemkin Stairs” in 1955 (following Stalin’s death in 1953 Kruschev came to power and then the names of the stairs could have been changed to reminisce the movie). Thanks to this name change and the incessant highlightening of their names in the Western media that these stairs contribute to the tourism of Ukraine.

Vladivostok Files

Constantine Feldmann, one of the rebels leading the paesant origine seafarers on board in 1905, was also in the cast. The story of Constantine Feldmann was particularly interesting. In order to understand his position let’s first look at what really happened in 1905.

In the Russo-Japanese War, which began in 1904, Japan was in a very bad situation and about to ask to truce. The British and US ships, which appear to be in neutral status in the Pacific Ocean were constantly reinforcing Japan. The Russian navy in the Pacific stopped some of these vessels, searched, withdrew them and detained in Vladivostok Port as they were seen carrying weapons, money and ammunition. Their crews stand trial in Vladivostok courts. Many of these case files were subsequently destroyed by the Bolsheviks. However, some of them have recently been discovered and published by Russian historians (footnote 3).

In Potemkin uprising, except Constantine Feldmann and a few officers, all peasant origin soldiers remained passive. The ship surrendered at the Constance Port in Romania. The crew are given the option either to return to Russia or to settle in other countries. Vast majority of soldiers returned to Russia and were all freed after trialss. At the end of the whole of this revolt story only the rebel in Potemkin Afanasy Matyushenko and the officer Piyotr Schmidt, who did not actively participate in the rebellion but also failed to comply the orders to shoot Potemkin was convicted to death and executed (Afanasy Matyushenko was captured in Russia after having a long trip all around Europe, in 1907) (footnote 3a). Constantine Feldmann escaped to England.

Constantine Feldmann published his memoirs about the ship revolt in England in 1908:

In order to understand how the 1905 Rebellions were fabricated within the context of external links, one must follow the traces of AngloSaxon + Japanese alliance inside Russia!

In June 1906 the Souvorin Publishing House in Saint Petersburg published a booklet entitled “The Illegal Side of the Uprising: Japanese Financing in Armed Uprisings in Russia“. In this booklet, the correspondences of Japanese military attaché Colonel Akashi‘s with Konnichi Zilliacus, leader of the independence of Finland, and George Dekanozi of the Georgian Socialist-Federalist Revolutionary Party during the first half of 1905, took place. These correspondences revealed Japan’s financing and weapon smuggling to the rebels. The publisher of this booklet wrote in his diary in 1907: “We were initially teased by this matter, but everything was true, I got these correspondences with the help of a Russian agent in Paris.” Konni Zilliacus of Finland, who was one of the main heroes of the incident, accepted these aids in the two volumes he published in 1919-1920. These contacts of Colonel Akashi could have only been uncovered in 1966, when Akashi’s reports had begun being opened up in parts by the Japanese government. Then they could have only been made public in 1988 by a team of three researchers, Inaba Chiharu, Olavi K. Falt and Antti Kujala (footnote 4).

Michael Futrell and John White also mentioned these aids in the midst of the 1960s.

It was understood from these reports that Colonel Akashi had performed all these activities following the instructions from Hayashi, i.e. the Japanese ambassador in England.

While the Russian police chief Leonid Rataiev and the Russian consul Bereznikov were concentrated in preventing the transfer of illegal publishings to Russia from Stockholm by bribing Swedish police and authorities, low-rank Russian policemen spotted the Japanese game and began collecting evidences. According to these evidences, Akashi’s contact with Russian socialists began in 1903.

This support had also been mentioned by Inessa Armand, who then became the lover of Lenin after 1909:

Following the Bloody Sunday Massacre on January 9, 1905 in Saint Petersburg, new protests were organised in Moscow. At that time Inessa was separate from her husband Alexander Armand, living in another district of the city with her lover and brother-in-law, Vladimir Armand. She sent a note to her husband Alexander Armand (who were in the far Eastern Russia, probably in Vladivostok, at those Russo-Japanese War days, for business or for some other reason, we don’t know…), mentionning the rumors of Japanese + AngloSaxon support to the rebels: “People talk about the Japanese hand in the uprising, that’s all bragging. We are doing this revolution, we are!” she wrote (footnote 4a). With that proclaim of Inessa, her husband Alexander Armand – who was a very wealthy fabricator – tied a red ribbon on his neck and called his workers at his factory to join the protests (footnote 5).

Here, the obvious question why a fabricator, a businessman, a boss, supports the labor movement, comes to mind. The Alexander Armand example was no exception, there can be shown many similar cases too. When discussing this phenomenon with my friend, director at the Arsenal Art Gallery in Kiev (who is also a Naum Kleiman fan) she argued: “Revolutions can not be done without financial support. Even Marx said that revolutions occur when nothing left to the lower classes except their chains and when wealthy people become unhappy in living as they lived before. So, revolutions happen when these two moments come together“.

Although this statement is partly true in theory, it becomes an awful Marx parody when it is presented as an explanation to concrete and specific events. It is even used as a theoretical curtain to cover up the actual intentions of individuals in action.

We first need to understand the roots of Armand family’s enmity to Tsar. His grandfather came to Russia in the Napoleonic period and started to work as an agricultural worker in a farm. He then built a business timber trade. The company grew very fast and the family got rich. Although there is no complete source on Armand’s family, we can procede in thinking about this timber trade which covers a wide range of Russian geography as one of the predominent business sectors. These sectors concerning the trade of fur, honey, hemp and timber are typically dependent to a foreign customer portfolio, mostly to Western Europe and the UK. This fact refers to the term used by Boris Kagarlitsky as to define Russia’s “semi-peripheral” status in capitalist world system. The big bourgeois class here is rather commercial, by contrast to the traditional European bourgeoisie which was predominantly industrial, i.e. it is not “nationalist”, but “globalist”, therefore, anti-centralist, a kind of “comprador bourgeois”.

Again, contrary to the Western (the “huguenot”/port bourgeois) model, the “petit bourgeoisie” in this geography is predominantly a heavy industry bourgeoisie which had rather nationalist and centralist tendencies. Compared to the West, it is late-developing and catching the former (the comprador-big Capital) from behind.

If we look at this action of Alexander Armand from a wider theoretical Marxist perspective, we can even argue that, apart from putting red tape and calling his workers for uprooting, he could even leave the key of his factory to his workers and still, he wouldn’t even loose anything substantial ! The “hardware” (the means of production, that is “hardware-Capital”, “Ch”) is the least important part among the means of production in the capitalist mode of production – as we mentioned previously in our article “Goose foot is comb-like”. You can confiscate all visible/material belongings of the boss. But you can not confiscate the “business cards” (contracts, credibility, relations). It is even difficult to confiscate money (crystallized labor, “Cm”), as it can easily be transfered to another geography as “financial capital” once it is detached from hardware-Capital, but even if you manage to confiscate it, “the business cards” – to say in more general terms – “the information capital” (or the “software-Capital”, “Cs”) remains still in Capitalist’s ownership.

That is how we can understand now Armand’s true motivation for calling his workers for uprising: Centralist Stolypin-Witte reforms were the greatest threat to their business. Should the Tsar were overthrown in this turmoil, the reforms would have stopped, the intermediaries, the local traders they were cooperating would regain power. At the worst case, they were confident that they would have been able to rebuild their business empire within a few years.

Let’s come back to Constantine Feldmann: Feldmann was able to re-enter Russia only after 1917. Then after he played in Eisenstein’s Potemkin Battleship film, we can not find any other information about what he did, in which other movies he did play or not, where he lived, etc. – except the fact that he disappeared during the 1937 Great Purge.

Kronstadt Trauma

The shooting of the Film was finalised and went into vision in Moscow, in 1925. Contrary to what is believed today, the film was only shown in Moscow and in just in a single cinema hall. And it only lasted for a week in the vision. It didn’t attract any public interest. At that time Hollywood films were being imported and people were more interested in these American films. It was removed from vision and thrown into storage. No articles, criticisms etc. were published about it. Moreover, the government did not support and promote the film even though it was the movie they ordered.

Sovkino’s president, Constantine Shvedshikov didn’t like Eisenstein at all. Still, apart from the fact that the film didn’t attract public attention, we should think about why the government did not promote the film: because they were afraid that this plot about the revolt in the navy could ignate public awareness on an important trauma, which took place just 4 years ago: The March 1921, Kronstadt Rebellion.

After the end of the Civil War, the Baltic Fleet – based in Kronstadt Island located in front of Petrograd – revolted. The insurrection took place on the ships Petropavlovsk and Sevastopol, led by Stepan Maximovich Petrichenko. They disclosed a 15-item wish list. The uprising was also supported by civilian people in Petrograd. As a general framework, their request list was largely overlaping with the project of the former Kerensky government: ask for free elections, freedom of speech, independent union organization for factory workers and right of the peasants to sell products in free market.

But still, rather than their request list, one should focus on the course of events prior to the rebellion:

One and a half years before this, in 1919, Petrograd was tried to be surrounded by British + Estonian joint attack from the west and by Archangel Operation (British + American + Canadian + French) from the east. Kronstadt marines defended the city heroically and repelled the attack. After the war was almost won with that local resistance that Trotsky sent reinforcements in October 1919, seamingly just to rescue the image.

Plus, just a year before these attacks of Entente Powers began, Trotsky had executed Admiral Shchastny with a claptrap prosecution (in 1918).

Trotsky’s procrastination in sending support to Petrograd and his signing an agreement with Britain soon afterwards beared doubts. In official socialist historiography, the Kronstadt Uprising is undercovered and when it comes to language, it is breefly defined as a “rebellion of peasant soldiers because of the civil war poverty”. The real reason however was more complicated: the doubt that they faced with a terrible betrayal at the top of the government!

In March 1921, however, Trotsky took immediate action. He excluded any possibility of any kind of negotiation with the rebels. He sent 25 000 soldiers under the order of Michail Tukhachevsky to destroy the insurgents immediately. On March 17, 1921, Tukhachevsky’s troops hesitated to attack their comrades, their gunmen in Kronstadt. The Cheka officers shot the hesitating soldiers from behind with machine guns… The loss of Tukhachevsky forces was 1400. A massive massacre took place: 1000 rebel soldiers were killed in the castle, 500 soldiers were taken prisoner who then ordered to be shot by Trotsky. It is also estimated that 2000 civilians were killed.

The NEP regime, which was adopted at the 10th Party Congress, just before the suppression of the Uprising, might not had a direct connection with the Kronstadt Uprising, but just creating an upsurge among rulers to enact immediate shaping of economic reforms. Here, however, one should investigate this possible relationship from the opposite side: The NEP may not be associated with the Rebellion as a program corresponding to the demands of the rebels, on the contrary, but the NEP may be one of the triggering causes of the Rebellion — if some details were made public and known before its enaction: Considering that Trotsky’s execution of Admiral Shchastny in 1918, right before the British + Estonian attack, his procastination in sending reinforcement to the defence of Petrograd in 1919, and his aggreement signed with Britain right after the defence should have already risen doubts and then the coming NEP granting privileges to foreign capital, especially to finance-capital would have been perceived as the last drop.

So as the Shutko’s too long screenplay about 1905 Protest was clipped and just the ship revolt part was taken, the film faced the Bolshevik gang with their Kronstadt Trauma.

Mayakovsky and the orchestrated polishing in Berlin

After the movie was thrown to the stock room, Sergei visited Sovkino with his close friend, Trotsky’s favorite poet, Vladimir Mayakovsky. Sergei took the film out of the depot and they watched it together with Mayakovsky (despite he was close friend of Sergei, Mayakovsky did not watch it in the cinema). Mayakovsky was not far from the world of cinema. He had also starred in “The Lady and the Hooligan,” directed by Yevgeny Slavinsky in 1918.

Having watched the film in the studio Mayakovsky stood up and said that this film was a masterpiece to be shown and watched everywhere. While getting out from Soyuzkino he was shouting: “I’m not through vet and I won’t be for at least five hundred years to come. Shvedshikovs come and go, but art remains. Remember that!”. Waclaw Solski (a Polish origine mate of Sergei) who was with Eisenstein and Mayakovsky at that moment, told this story to the Commentary in 1949.

After Mayakovsky’s outburst, some members of the Bolshevik party and journalists watched the film and decided to send it to a film festival in Berlin, in 1926. The Prometheus film company in Germany was commissioned and purchased the negatives. But, since the movie sucks, it should be radically re-organised to be shown in Europe. The original length of the negatives before trimming was 45km (footnote 6a). The company hired the famous German director Piel Jutzi to trim and reshape the negatives (footnote 6b).

Following a good PR organisation, the show in Berlin took place in Ufa-Palast am Zoo, on December 17, 1926 (footnote 6): famous star and owner of Hollywood’s Universal Studios Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and his wife Mary Pickford, along with ambassadors and consuls from various countries joined the gal. On exit, Mary Pickford couldn’t even talk but crying while Douglas Fairbanks Sr. was telling the journalists how fascinating was the Film. It was that way that Sergei Eisenstein was made famous in the world in a single night, by leaving out of account all the staff that worked behind the scenes.

The music of the film was composed by Edmund Meisel, a close friend of Bertold Brecht. The New York Herald Tribune newspaper from the other side of the world reported how magnificent was the music of the film by publishing an article on it.

It is also worth to note here that this Edmund Meisel’s original music was lost during Wold War II and that “Enno Patalas version” that was shown at the Berlin Film Festival in 2005 – which was allegedly much better than the one shown in Trafalgar a year before – was also a reconstruction made from scratches (footnote 7).

The film was then banned in some cities in Germany. Protests started against the censor. The court allowed to play film on the condition to cover the face of the cruel Cossack soldier and cut the sea officer’s sea-throwing scene. Despite this court decision, the German Ministry of War prohibited the film to its officers and soldiers.

The US forbade it to naval officers and soldiers. France burnt all copies and prohibited its viewing. England was the first country which censored the film with concern that it would ignate strikes in 1926 and its prohibition remained into effect until 1954. Even after 1954, it has allowed in condition to cutting some scenes, until Ken Livingston’s Trafalgar demonstration in 2004. It is again an interesting fact that the film has never been censored in Turkey.

After that kind of “success” of Sergei Eisenstein + Grigory Alexandrov in Potemkin Battleship film, they tried to raise the third part, “October” for the 10th anniversary of the Revolution by Stalin’s order. They took advantage of John Reed‘s “10 Days that Shook the World” book. But the movie sucked again. It was again thrown to stock room soon after its first viewing. A rather recent comment on this film in The Guardian, written by Peter Bradshaw, attempted to define the hidden geniousity in the film by these words: “re-inventing history through hallucinations …“. This expression draws us to uncertainty on whether Peter Bradshaw appreciates or derrogates the film (footnote 8). Scenes from close ups show similarities to the insane faces in Kubrick’s “Shinning” movie. This strange thing that came out from their project to praise revolution scared even Stalin.

Stalin, however, did not give up ordering new films to Sergei + Grigory team as they did not give up their struggle in making new films too. After a year, Stalin gave them a new film order to praise the new centrally planned collectivist agriculture and livestock economy politics, the Kolkhoz system. This movie was entitled as “Generalnaya Liniya” (General Line) was too thrown to stock room even without being shown in the cinema for a single day, since it rather exhibited the misery of kolkhoz farms instead of showing their success. The reason of the censor by the government for this film which was also ordered by the government was defined as “wrong ideology”.

Again as a reward for these “successes” in their work, Sergei Eisenstein and Grigory Alexandrov were then sent to Europe in 1929 . They gave lectures in various institutes in Germany, France and England.

Meanwhile a very affluent businessman named Leonard Rosenthal (migrated to Paris from Russia, dealing with trading of pearls worldwide) was in love with a Lithuanian origin French bar singer Mara Griy. Rich businessman thought that he could do a very romantic gesture in making a movie for his great love. By that way, he wanted to immortalize his great love with Mara. For this purpose, he applied to Eisenstein + Alexandrov team. Mara Griy was made to sing in this movie called “Romantic Sentimentale”.

This movie however, surprisingly had a great success: his wife divorced Leonard Rosenthal and the lovers finally managed to get married. We kindly ask you to show patience and watch this single successful film of Eisenstein to the end:

Connection to Trotsky via Frida Kahlo

We already mentioned above that Eisenstein first started in his career in Proletkult theaters and that Mary Seton, a – so-called – prominent biographer of Eisenstein, for whatever reason, avoided expressing the conflicts and disputes within Proletkult.

In fact, the history of this confrontation goes back to 1908. For now, we can distinguish one of the opposing camps of this conflict by names such as Lunatcharsky + Bogdanov + Kollontai. This camp rejected categorising art as bourgeois or proletarian. They gave support to Grimm Peace Plan in 1916. They defended a libertarian biopolitics defending sexual freedom.

By contrast, the camp that we can identify by names like Lenin + Trotsky + Kamenev + Bukhanin + Rykov and Trotsky’s sister Olga Kameneva who was made married to Kamenev, excluded all compromises, defended the destruction of the architecture of the Tsarist period, appropriated the doctrine “Art is a slap to the taste of people! ” and they harshly imposed this doctrine.

The conflict between these two camps manifested itself in almost every arena: for example, the first camp advocated contraceptive, defended free sexuality and the right of abortion for women (Kollontai). The second camp however was even against birth control (Olga Kameneva).

The first camp’s priority during the Civil War was the defense of the country and they showed anti-imperialist reflexes, while the second camp used to hide behind high socialist ideals and blurred theorisations like “permanent revolution” in cooperating with imperialist invaders.

The contradictions that began over this split resulted first in the liquidation of the real socialists (the first camp) by the obscurantist Bolsheviks (the second camp), and then, the liquidation of the obscurantist Bolsheviks (the second camp) by Stalin’s restoration. Common people struggling with hunger, epidemic diseases, watched the events from afar in misery and had greatly suffered from what was going on.

Eisenstein had managed to survive in both of these liquidation due to the fact that he was just a depolitized and unqualified employee following the orders from rulers.

The personal relationships of the names surrounding Eisenstein – like Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, Esenin and his wife Zinaida Reich – to Trotsky are well known and explicit, during the period when the film Potemkin Battleship was made (footnote 9). But Eisenstein and his colleague Grigory Alexandrov themselves do not appear to be directly connected to Trotsky – except that Trotsky had a script displayed in the film Potemkin, which was then altered to a Lenin’s word by the order of Stalin. We can only reveal this connection indirectly, through Frida Kahlo‘s husband, Diego Rivera.

In April 1930, one of the partners of Paramount Pictures, Jesse L. Lasky, bid $ 100,000 to Eisenstein + Alexandrov team for them to make a movie. So, they move to Hollywood.

As Eisenstein procastinated the job asserting that he was doing “art for art”, the deal became suspended. Meanwhile, he gave speeches at Harvard and Columbia universities. Eisenstein could not produce a coherent scenario within the given time and the project is canceled.

Was one reason for their disagreement here, Frank Pease, nicknamed “Major”, who was at the head of Hollywood Technical Directors Institute and who was known by his anti-Bolshevik stance ? Indeed, right after the dissolution of the deal with Lasky, the American “socialist” writer Upton Sinclair – who was known as the enemy of Frank Pease – ordered Eisenstein a film dealing with the revolution made by middle class people and peasantry against Porterio Diaz’s dictatorship in Mexico. Meanwhile, the Zapata Revolution in Mexico had already failed and an anti-communist government came to power. The United States was deporting Mexican-origin refugees to their country. In these circumstances that Upton Sinclair sended Eisenstein to shoot that film in Mexico.

With the initiative of Major Frank Pease, Eisenstein and his team were detained in Mexico. Many celebrities including Douglas Fairbanks Sr. (who first made Potemkin famous in Berlin), Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw and physicist Albert Einstein called to the Mexican government for releasing the team. Consequently, they were freed. It was in this process that Eisenstein met Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, the well-known names of the Trotskyist inteligensia in Mexico (footnote 10). These acquaintances of Eisenstein then spread to other members of this circle like Jean Charlot, Roberto Montenegro, etc..

They had very enjoyable days in Mexico. Eisenstein was even given a guide. With this guide, Palomino Canedo, Eisenstein had an intense and deep relationship – as Peter Greenaway satirized Eisenstein’s Mexican days in “Eisenstein in Guanajuato” in 2015. Peter Greenaway made this film at exactly at a time when the news (or propaganda) about the discrimination and torture against gays in Chechnya, the prohibition of “Gay Pride” parades in Russia, were brought to world agenda.

This bohemian life in Mexico cost three times more money than the agreed budget with Sinclair. He shot 61km film negatives in 14 months. However, despite this emormous length of negatives he used, no piece was adequate for making a film (except Grigory Alexandrov’s compilation “Que Viva Mexico” and two other versions compiled in the later years). The patience of Upton Sinclair‘s wife, Mary Craig Sinclair exhausted and the funding was cut off. Since no money was sent from the Soviets and following the personal telegram of Stalin, the team had to return home, to Moscow.

This point is important to us. Because the last stop of Trotsky was again that same house of Diego Rivera + Frida Kahlo couple. After having been sentenced to death in his absentia in Moscow, Trotsky became finally hosted by this couple and his guesthood was five years after Eisenstein’s visit to them. Hereunder are very rare camera shots of this romantic quartet:

In Diego Rivera’s “socialist” art, we find all the paradoxes typical to Trotskyism at a micro level:

On May 26, 1937, Ford factory workers rallied in Detroit. According to Linda Bank Downs, a “Diego Rivera expert” scholar, workers had risen because of unemployment, asking the Ford factory to be recruited (which looks like an opposite case of “strike” phenomenon). According to other accounts, the stake was standard requirements such as reducing the 8-hour working time to 6 hours and wage increase.

Stories that are told in various sources about the continuation of the event are much more confusing:

The World Socialist Web Site (wsws.org), known for Trotskyism, claims that Diego Rivera’s wall paintings were very popular among workers. But on the other hand, Edsel Ford (the only known legitimate child of Henry Ford) was the sponsor of Diego Rivera! (footnote 11). Again, according to Linda Bank Downs, during this uprising which resulted in beatings and deaths, Diego Rivera intervened and employed these workers (did he employ them in the museum, or told to boss to hire them in the factory, or let them paint his own new paintings … this point is not clear in the writings of Linda Bank Downs (footnote 12).

When we look at the course of events, we see that Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova settled in the house of Diego + Frida couple in January 1937. The events that are called as “Battle of the Overpass” in Detroit erupted when Trotsky and Frida had a love affair. But whether or not Frida’s love with Trotsky was her revenge against Diego’s affair with her sister Cristina Kahlo still remained a question mark.

In the context of this love polygon and possible political engagements of Trotsky in America, we can see that there could have been many other perpetrators for the killing of Trotsky on August 21, 1940 prior to Stalin’s agents. There is of course no doubt that Stalin contemplated this assassination with great pleasure, even if the perpetrators were not his agents. The killers fled to Russia and were rewarded with badge. The facts will be revealed as archives are opened and historians work.

Whether or not there was a connection between Trotsky and the workers’ uprising in Detroit, and what kind of connection it was, is a matter that still in need to be investigated today. There is also no comprehensive and consistent source on this “Battle of the Overpass” in Detroit. These are the darkest and most shitty pages of socialist history.

Of course, the issue we are focusing on here is not the private lives of people. We investigate how this “art” inteligencia, who had been living a luxury-bohemian life with capitalist’s fodder and hiding behind “high ideals” and theories derived from Marxism, became vehicle for strategies to manage masses in global scale.

Ghost writer Jay Leyda and MoMA

Jay Leyda, who made a film called “A Bronx Morning” in 1931, was accepted as student to Moscow State Film School which was founded by Eisenstein and colleagues in 1932.

It is stated that Jay Leyda was a high school graduate. He worked with Ralph Steiner, a photographer in New York City … Taking into account his writings style, elaborate language he uses, the fact that he taught at famous American universities as professor at his later years, the fact that he was seen as an authority around the world on Emily Dickinson and Herman Melville, we are suspicious of the allegations that he had no academic career. It is even more logical to define his student-teacher relationship with Eisenstein was on the opposite way: as a teacher-student relationship.

We do not know how Jay Leyda followed lessons taught in Russian at the Moscow State Film School and whether he knew Russian or not. All correspondences he made with Eisenstein were in English.

Jay Leyda married Si-Lan Chen in 1934 two years before returning to the United States in 1936. Si-Lan Chen‘s father was the secretary of Sun Yat-sen. Sun Yat-sen is a Chinese statesman who is regarded as the father of modern China, who had played an important role in the fall of the Chinese Empire and had been President. When Mao came to power, the family escaped to Moscow.

Si-Lan Chen was a well-known modern dancer of her time. She was known as the expert of biomechanical modern dance techniques developed by Meyerhold. Meyerhold is known as being Trotskyist.

As soon as he returned to New York with his wife, Jay Leyda founded the film division of MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), an organization also known as Trotskyist.

In a variety of sources it is said that Jay Leyda had taken Eisenstein’s articles with him as he returned to home and compiled, edited and published them in the US. However, we think that Jay Leyda should have done much more than just editing Eisenstein’s writings: he was most probably the “ghost writer” of Eisenstein.

Eisenstein’s correspondence with Jay Leyda continued uninterruptedly until Eisenstein’s death in 1948.

Connection to Stalin via Lyubov Orlova

Sergei Eisentein married Pera Atasheva in 1934. The next year of his marriage, in 1935, he made “The Bezhin Meadow”, which was supposed to be as a new rhythm experiment. This film was not a moving shot, but rather the consecutive display of a series of photographs. Officials did not like the film, the project was stopped as it was ruining the budget and the negatived were again removed to stock room. The Film had no other copy. During the World War II the negatives were damaged (We will present later in appendixes, the story and discussions about this film concerning the course of events to bring Boris Shumyatsky and Isaak Babel to execution).

Pera Atasheva cleaned up the burnt parts of the negatives and compiled a 35 minute film. This film, which was not considered as worth to be shown in the Soviets, has been “discovered” after many years and became the honorable guest of the 2018 Cannes Film Festival.

Having finally ruined all his credibility by Stalin, Sergei could not get permission for his new projects such as the Spanish Civil War and the Red Army.

However, in 1938 it happened a surprising development: “Alexander Nevsky” was commissioned to him. How come that Sergei Eisenstein was able to undertake this project after so many failures and among dozens of more qualified Soviet film directors?

In 1933, Sergei’s partner Grigory Alexandrov married Lyubov Orlova. Lyubov Orlova was a very beautiful woman. Stalin had a special interest in Lyubov Orlova. She had been summoned to all invitations in Kremlin and was often being called by Stalin himself. Lyubov Orlova was also a very close friend of Sergei, like his husband Grigory. Thanks to Stalin’s special interest in Orlova that the team managed to get the order. This fact, which was clearly expressed in Russian newspapers of the time, was also spoken in the Western press (footnote 13).

The tension between Lyubov Orlova and her stepchild (the son of Grigory from his first wife) never ended. This alchoholic child in rage, sold the dacha (cottage house) which was left to him after the death of his father and his stepmother, without touching anything in it. The house was bought by a wealthy doctor, with a large archive in it. Although the content of this archive has not yet been described in detail, circles that are concerned about its revealing have expressed this relationship (footnote 14).

The film tells the struggle of Russia’s founding hero, Alexander Nevsky against Germanic tribes, the Teutonic Knights that symbolize today’s Germans. Swastika was shown in the hands of Teutonic Knights and on their tents. The project was supported by the Minister of Cinematography, Ivan Bolshakov.

In this commission – we think Orlova was the intermediary – was it sought to send a message to the Western world about the ongoing Russian X German tension, as Sergei was already known as having many external connections, including Jay Leyda?

The shooting of the film ends on 1 December 1938. However while it was expected to immediately enter the vision, the vision of the film was postponed by an order from above – in the meanwhile some copies had been sent to Western countries, including the USA. In August 1939 the Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty was signed and the Film was thrown to stock room (to Mosfilm storage).

It was only after two years that the film was shown, when USSR was attacked by Germany.

At the end of the film, Alexander Nevsky says, “We are always open to our guests who come to us for peace and commerce, but those who attack our country will receive such a response from us that their pigs can not even put a nose into our garden!” These words were almost identical to those of Stalin’s speech in 17th Party Congress (1934). Following these messages sent by the USSR one after another, one of the pigs in the novel Animal Farm, written by George Orwell in 1943-1944, was symbolizing Trotsky.

The music of the film was composed by Sergei Prokofiev, one of the best students of Rimsky Korsakov. Western reviewers had highly acclaimed this film on the days it was shown. However it is then regarded as an unfavorable film by the British and American media after 2000 (they all use the same term “infamous” in a coordinated way, to define it).

His last film, Ivan the Terrible (I and II), was again made with the help of Grigory Alexandrov and his wife Orlova. This opera-style film was again unfavorable. Finally, Stalin had asked to film his life in three parts, but he died of a heart attack while this was in the project phase.

After the death of Sergei, his wife Pera Atasheva continued to live in Moscow’s Smolenskaya office until her death in September 1965. After Pera was dead, this flat of Eisenstein was transformed into a museum full of books, drawings, letters and other special items. The flat became a frequent destination for foreign intellectuals who traveled to Moscow. In Russian newspapers, the expression “The Mecca of intelligentsia” was used for this private house-museum.

In 2015 The European Film Academy rewarded this museum in Smolenskaya as one of the “European Cinematic treasures”. The house of Lumiere Brothers in Lyon, the home of Ingmar Bergman in Faro Island, the house of Tonino Guerra in Penabilli and the Potemkin Stairs in Odessa too, were granted as treasures in the same vein.

At the beginning of 2018, the Union of Filmmakers (Союз кинематографистов Российской Федерации), headed by Nikita Mikhalkov closed the museum-apartment and removed the items to the warehouse, to be exhibited in a museum of Russian cinema that will be founded in future. While these events were happening, the former director of the Moscow State Center Cinema Museum (Государственный музей Центрального кино), Naum Kleiman – a fan and a world scale expert on the subject of Sergei Eisenstein – was somewhere very far from Moscow.

Theoretical depths, sublime ingenuities …

Starting from 2004 Trafalgar Show, we have seen a rising new wave of Potemkin Battleship and Eisenstein hysteria in the Western left-intellectual and art circles. As well as it has being shown in many film festivals, on January 22, 2018 Google invented the necessity to celebrate the 120th birthday of Sergei Eisenstein by a doodle.

Meanwhile, Marie Rebecchi of Udine University and Elena Vogman from The Free University of Berlin found Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico film “overly scientific”. In 2017, they created an exhibition entitled “Sergei Eisenstein: The Anthropology of Rhythm” in Nomas Foundation in Rome, making the necessary scientific explanations in the catalogue of the exhibition, for those who do not understand the film.

Eisenstein, in his writings on the assembly techniques, instilled the thesis of the British-born American psychologist Edward B. Titchener saying that “at least two perceptions must come together to make a sense” to cinema technique (footnote 15). But as we already detailed above the educational backgrounds of Jay Leyda compared to Eisenstein’s, that student – teacher relationship between them could have been reverse. So, this “theoretical depth” in Eisenstein had most probably been the fabrication of Jay Leyda.

It is also known that the “prestigious” experts, the art theorists, who write on Eisenstein have linked the theory of Ferdinand de Saussure to Eisentein’s film theory exhibited in “Film Form”. The themes such as “difference” between signifier/signified couples were necessary for semantic fixation (to build a meaning) and that the differences between film frames and the crossing over these differences with rhythm, are then processed and elaborated in the writings of Jacques Derrida in the 1960s. Eisenstein “experts” point to this anachronistic situation – as “beyond of his age” – and they thus find a way to mount an ingenuity to Eisenstein. However, the actual state of things are again much different than these sublimated scholastic assertions:

That book “Film Form”, which is said to belong to Eisenstein, was supposedly compiled from the essays written by Eisenstein between 1928 until 1945. But for whatever reason, Jay Leyda had waited not just until Eisenstein’s death in 1948, but until 1951 to “compile”; to “edit” and to publish these writings: six years in total. Why? For us, this “theoretical depth” or rather the intellectual patchwork of Saussure filled by fragments from epistemic coherentism, were again the fabrication of Jay Leyda.

The fabrication here however was not simply a theoretical imagination. It was an inteligensia operation to manufacture a myth out of thin air (a very similar process to that of FED’s printing banknotes out of thin air) endoctrinating masses with a mystified romanticism associating productive and positive “contingencies” to mass movements – “singularity” in Derridean terms. When we say “contingency” here, this philosophical jargon corresponds to positive expectations when the “event” begins and yet we do not know how it will end. The common leftist philosophical discourse says that It is only after it happens that (retroactively) we can attribute its outcomes to the event as the event changes us too during its happening (double-hermeneutics). This discourse attributing inner positive potentials to mass movements has two contradictory dogmatic aspects:

1) it leads to constant infantilization of masses assuming that they would learn by practice and then avoid their past mistakes;

2) it assumes that mass movement has an inner wisdom and leads to the expectation that this subject-mass (the so called “political subject”) constant learning process will bring a better future, i.e. optimism.

By contrast our job here is to keep the track of how these “contingencies” are being manufactured in rulers’ (not people’s) minds and the way their imposed doctrines blur understanding social phenomena in their simplest factual nakedness and banality. By attributing such mysterious “wisdom” to masses, indeed, intelligentsia derives a kind of intellectual enjoyment in distinguishing its priviledged status from masses too.

We see that this “philosophical” trend, which mounts the concept of “event” in Heidegger, Derrida, Arendt and Badiou to the supposed ingenuity of Eisenstein, begins in 1990’s, overlapping with the rise of neo-con Trotskyism. Typical examples in this issue include Julia Vassilieva‘s “Between Utopia and Event: Beyond the Banality of Local Politics in Eisenstein” and Jason Lindop‘s “Eisenstein: Intellectual Montage, Poststructuralism, and Ideology” articles (footnotes 16 and 17).

When we look up Derrida – whose work was hardly to be defined as “Philosophy” since it procedes through blurred ascriptions rather than precise logical argumentations – we identify his connection to this circle through Charlie Chaplin: Jacques Derrida is given by the name of Charlie Chaplin’s spiritual son Jackie Coogan. Derrida’s philosophy evolved over time among these figures belonging to the same intellectual circle and then retroactively attributed to Eisenstein to mount him “ingenuity”.

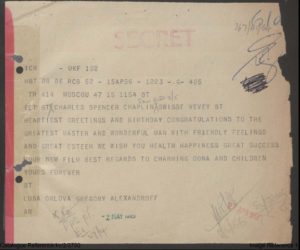

Hereunder is the birthday celebration message from Eisenstein’s closest colleagues, Grigory Alexandrov + Lyubov Orlova couple, to Charlie Chaplin:

http://www.discoveringchaplin.com/2015/03/chaplin-with-russian-director-grigori.html

The evident question that comes to mind about this telegraph, what MI5 was looking for about Charlie Chaplin and why MI5 holds a Charlie Chaplin file? The answer of the Trotskyist “left” would typically be simple: “These people are the artists, art is a threat to political power and order, so the states monitor closely the artists” … Let us accept this simple explanation as a first step. It defines the situation as a very ordinary one and disregards any attempt for further investigation. And then, let’s focuse on the second premise of this argument, which has been taken for granted by sleight of hand: To whose power is it threat in this particular case? Let’s presume that MI5 keeps a file of Charlie Chaplin because it perceives him (or his art) as a threat to the British Empire or to the world order … But aren’t these closest colleagues of Eisenstein, Grigory Alexandrov and Lyubov Orlova sending birthday message to Chaplin were themselves hired by Stalin for making films just to send diplomatic messages to the West! Now let’s look at how these high socialist ideals manifesting in their art – supposedly threatening states, empires – shift when things go wrong, when there is no “permanent revolution”, “world revolution” etc at sight in the UK, US … so then, who is threatened by whom? What if the state apparatus hold a file of Charlie Chaplin and the like, because it also accounts for how these ties within art circles could also be instrumental for their imperialist projects? But the time was changing. Eisenstein’s team was changing too. And when Eisenstein and his team returned home from the US, Stalin too was making similar calculations right from the opposite side. So do we see that these “artists” – rather than posing a real threat to power – they were just vehicles of power.

An exhibition entitled “Sergei Eisenstein, Drawings 1931-1948” was held at the gallery of Alexander Gray Associates in London from 7 January to 11 February 2017. In this exhibition’s catalogue, Naum Kleiman described these drawings that were used as a secret communication method in the years when homosexuality lived in secret and faced great reaction, as “art masterpieces inspired by authentic Mexican art.”

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, described the film Potemkin Battleship as the most successful propaganda masterpiece in history. Goebbels was right in this determination for the film Potemkin Battleship. These ambiguous ideological symbols pointing to mystical ingenuities that ordinary people can not understand, unrecognizable theoretical depths and authenticities that are just understood by an intelligentsia having also the privilege of living in discrete, inaccessible tastes, doesn’t remind you just another version of ecclesiastical elite or judaistic or islamist rabbinate? Every kind of ideological sublimation is derived from such ambiguous, mystical discourses of the priviledged intellectual class. When these “greatnesses”, “ingenuities”, “incomprehensibilities” are turned down, that is, when the feet land on the earth (or ditch on the water), we face the slaughter in Kronstadt, millions dying by starvation, one of the greatest betrayal of history.

The Log of Revisions:

- 14 November 2021: The footnote (6b) has been added as for the documentation for the fact that the publicly known version of the film The Battleship Potemkin was the creation of Piel Jutzi and not that of Eisenstein. Although the work of Dušan Radunović offers an account of the revisions made in the post-War period (and being by no means an exception in vernishing the fabricated “geniusness” of Eisenstein), it still dares referring, at least slightly, on this untold aspect.

- 5 October 2021: The previous YouTube link (https://youtu.be/45Z0keLaGhQ) displaying the Mexican days of the “romantic quartet” was disappeared from the YouTube broadcasting for some unknown reason. We found however the same video in another YouTube link (https://youtu.be/pIBRynm5Xtc) and replaced the previous one with the new one.

- 8 January 2021: The reference concerning Inessa Armand’s letter to her husband (telling him “it’s not the Japanese, we are doing this revolution!” about the 1905 Revolts) is made by the footnote 4a. In our upcoming studies, we will investigate the fabrication of 1905 Riots by Imperialist countries and how Inessa and her stablemates were involved in this fabrication. Besides, a note concerning Kronstadt Uprise, about a private communication with a professor (who contributed to our research with valuable information) was mistakenly mentioned in the text. This part has been removed.

- 01 October 2018: Additional clarifications are made regarding the chronological coincidence of the Trafalgar show and the “Occupy Square” trend, as a reply to the fruitful criticisms coming from colleagues.

- 17 August 2018: The detail that Potemkin film’s negatives were 45km in length. By implication, we can see how big was the material transferred to Piel Jutzi and how different was the final version of the film that we know today (which is compiled by Piel Jutzi and not by Eisenstein), from the original version made by Eisenstein’s team.

- 13 August 2018: The monk-intellectual doctrine which attributes to the mass movements a positive, optimistic potential have been investigated under the subtitle “Theoretical depths, sublime ingenuities…” through its inner inconsistencies and contradictions.

- 10 August 2018: The detail about Afanasy Matyushenko is added.

- 03 August 2018: The birthday celebration message of Orlova+Alexandrov couple to Charlie Chaplin, that is obtained from an MI5 file, has been added to the last section evaluating the “philosophy” of Derrida.

- 30 July 2018: A separate section has been elaborated on the theoretical-philosophical concoctions associating Derrida and Saussure to Eisenstein. Two reference articles has been used as samples for developing a critique to such approaches.

- 28 July 2018: The paragraph questioning a possible causal link between the Kronstadt Rebellion and NEP has been added.

- 27 July 2018: The work of N.Swallow (1976) has been referred in the section about “the theoretical depth” of Eisenstein, the eclectic and circular mounting of Saussure’s semiology through Charlie Chaplin and Derrida and then back again to Eisenstein. The references of Crystal Downing and Peggy Kamuf are given.

- 25 July 2018: The dates of the photos about the “Three big street parties”, that are the photos of Kiev Maidan and Tibilisi, are corrected — upon the irrelevant criticisms showing the false dates for falsifying our argument.

Footnotes:

1) Marie Seton, “Sergei M. Eisenstein”, Grove Press Inc, New York, First Evergreen Edition, 1960, p.63.

2) N. Swallow, “Grigori Alexandrov in Eisenstein, a Documentary Portrait”, 1976, in “TEACHERS’ NOTES, GCSE Media Studies, A’Level Film Studies and GNVQ Media: Communication and Production (Intermediate and Advanced)”.

3) British Assistance to the Japanese Navy during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, The Great Circle, Australian Association for Maritime History, Vol.2, No.1 (APRIL 1980), pp. 44-54

3a) David Eduardo Nassau, “Sergey Eisenstein : The Use of Graphic Violence in “Strke” and “Potemkin””, B.A. International Relations’ Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, December 2013

4) Inaba Chiharu, Olavi K. Falt, Antti Kujala, “Rakka Ryūusui: Colonel Akashi’s Report on His Secret Cooperation with the Russian Revolutionary Parties during the Russo-Japanese War.”, Societas Historica Finlandiae, Helsinki, 1988.

4a) И.Ф.Арманд — А.Е.Арманду из Пушкино на Дальний Восток, 14 января 1905 года, Новый Мир, #6 июнь 1970г., стр.203

5) Лариса Прошина, “Ленин-Крупская-Арманд”, Свидетельство о публикации №214032500102, 2014.

6) Fiona Ford, “The film music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)”, PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, 2011.

6a) Nassau, ibid.

6b) The work of Dušan Radunović, “The shifting protocols of the visible : the becoming of Sergei Eisenstein’s “The Battleship Potemkin”.”, Film history, 2017, 29 (2). pp. 66-90, republished by Durham University, in 24 July 2017.

7) Bruce Eder, Biography of Edmund Meisel, https://www.allmovie.com/artist/edmund-meisel-p163004

8) Peter Bradshaw, Hallucinating history: when Stalin and Eisenstein reinvented a revolution: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/oct/24/october-revolution-stalin-sergei-eisenstein

9) Clive Barker, Simon Trussler, The Trial and Death of Meyerhold, New Theatre Quarterly 32: Volume 8, 1993.

10) Mike O’Mahony, “Sergei Eisenstein – Critical Lives”, Reaktion Books, London, 2008.

11) Tim Rivers, David Walsh, Eighty years of the Diego Rivera murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts, 5 September 2013: https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2013/09/05/mura-s05.html

12) Linda Bank Downs, “Rivera, Detroit Industry Murals”, undated: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/art-between-wars/latin-american-modernism1/a/rivera-detroit-industry-murals

13) Brian Matthews, The baleful life of Stalin’s favourite actress, 30 January 2014: https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=38858

14) “Любовь Орлова: «Я была любимицей Сталина, но не любовницей!»”: https://7days.ru/stars/privatelife/lyubov-orlova-ya-byla-lyubimitsey-stalina-no-ne-lyubovnitsey.htm

15) J. Dudley Andrew, The Major Film Theories – an introduction, Oxford University Press, 1971.

16) Julia Vassilieva, “Between Utopia and Event: Beyond the Banality of Local Politics in Eisenstein”, in Film Philosophy, vol 15/1, p. 140-160.

17) Jason Lindop, “Eisenstein: ‘Intellectual Montage’,

Poststructuralism, and Ideology”, Off Screen, Volume 11, Issue 2, February 2007

Bibliography

Poststructuralism, and Ideology”, Off Screen, Volume 11, Issue 2, February 2007